What are Schedule Health Metrics?

At the heart of every successful Earned Value Management System (EVMS) is a comprehensive Integrated Master Schedule (IMS) that aligns all discrete effort with a time-phased budget plan to complete the project. As such, the IMS must be complete and accurate to provide the necessary information to other EVMS process groups and users. The IMS may be a single file of information in an automated scheduling tool, or a set of files that also includes subcontractor schedules.

At the heart of every successful Earned Value Management System (EVMS) is a comprehensive Integrated Master Schedule (IMS) that aligns all discrete effort with a time-phased budget plan to complete the project. As such, the IMS must be complete and accurate to provide the necessary information to other EVMS process groups and users. The IMS may be a single file of information in an automated scheduling tool, or a set of files that also includes subcontractor schedules.

For any medium to large project, the IMS may contain thousands of activities and milestones interconnected with logical relationships and date constraints to portray the project plan. Schedule Health Metrics provide insight into the IMS integrity and viability.

Why are Schedule Health Metrics important?

For a schedule to be useable, both as a standalone product and as a component of the EVMS, standards have been developed to reflect both general scheduling practices and contractual requirements. Schedule Health Metrics contain checks designed to indicate potential IMS issues. Each check has a tolerance established to help focus on particular areas of concern. The individual metrics should not be considered as a pass or fail score, but should be used as a set of indicators to guide questions into specific areas of the IMS.

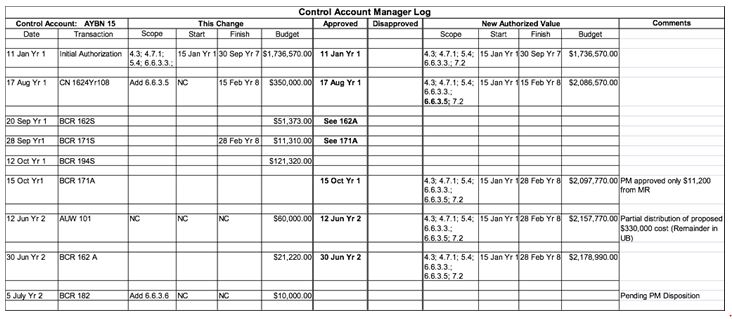

For example, if there is an unusually large number of tasks with high total float properties, a review of the logic in the IMS is warranted. At the end of the analysis, if the Control Account Manager (CAM) responsible for the work, with the help of the Planner/Scheduler, can explain why the high float exists, then the issue is mute. Metrics are simply a method to help isolate issues in a large amount of data. In this example, the analysis will continue to depict issues with this CAM’s data, but those issues are not indicative of failure.

What are the standards?

From the beginning of automated scheduling systems in the 1980’s, attempts have been made to take advantage of the scheduling databases for the purpose of metrical analysis. The maturity of scheduling software tools has provided better access to metrics in both open architecture databases and with export capabilities to tools such as Microsoft’s Excel and Access products. With the availability of the new tools, new analysis techniques were developed and implemented.

Several years ago, the Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA) reviewed the various Schedule Health Metrics being used within the US Government and selected 14 tests they believed to be the best tests of an IMS. Because they support a wide variety of customers from the DOD, NASA, and DOE, they have developed these checks with thresholds that should be common to all types of programs, but not specific or restrictive to a particular one. The thresholds help bring focus to the issues in the schedule under review. With agreement between the customer, the DCMA and the contractor, they may be altered in some cases to reflect the unique nature of a project.

Unless otherwise indicated, the DCMA Health Metrics apply only to incomplete activities or tasks in the IMS, not milestones, with baseline durations of 1 day or longer. This set also excludes Level of Effort (LOE) and Summary tasks because they should not be driving the network. The DCMA 14 point Schedule Health Metrics are:

1. Missing Logic

The test: The percentage of incomplete activities that do not have a predecessor or successor.

The threshold: 5%.

For a schedule to function correctly, the tasks must be logically linked to produce a realistic mathematical model that sequences the work to be performed.

2. Activities with Leads

The test: The percentage of relationships in the project with lags of negative 1 day or less.

The threshold: 0%.

The project schedule should flow in time from the beginning to the end. Negative lags, or leads, are counter to that flow and can make it more difficult to analyze the Critical Path. In many cases this may also indicate that the schedule does not contain a sufficient level of detail.

3. Activities with Lags

The test: The percentage of incomplete activities that have schedule lags assigned to their relationships.

The threshold: 5%.

An excessive use of lags can distort an IMS and should be avoided.

4. Relationship Types

The test: The percent of Finish to Start relationships to all relationships.

The threshold: 90%.

A project schedule should flow from the beginning of the program to the end. Finish to Start (FS) relationships are the easiest and most natural flow of work in the IMS, with the occasional Start to Start (SS) and Finish to Finish (FF) relationship as required. Start to Finish relationships should not be used because they represent a backward flow of time and can distort the IMS, as do the overuse of SS and FF relationships.

5. Hard constraints

The test: The current definition includes any date constraint that effects both the forward and backward pass in the scheduling engine. These include any date constraint that says ‘Must’ or ‘Mandatory’, ‘Start On’ or ‘Finish On’, and ‘Start’ or ‘Finish Not Later Than’ date constraints.

The threshold: 5%.

Hard constraints limit the flexibility of the IMS to produce reliable Driving Paths or a Program Critical Path. Techniques using soft constraints and deadlines can allow the schedule to flow and identify more issues with float values.

6. High Float

The test: Percentage of tasks with High Total Float values over 44 days.

The threshold: 5%.

A well-defined schedule should not have large numbers of tasks with high total float or slack values. Schedules with this condition may have missing or incorrect logic, missing scope or other structural issues causing the high float condition. The DCMA default threshold of 44 days was selected because it represents two months of effort. Individual projects may wish to expand or contract that threshold based on the length of the project and the type of project being scheduled; however, any changes in thresholds should be coordinated with the customer first to confirm the viability of the alternate measurement.

7. Negative Float

The test: The percentage of activities that have a total float or slack value of less than zero (0) days of float.

The threshold: 0%.

When a schedule contains tasks with negative float, it indicates that the project is not able to meet one or more of its delivery goals. This is an alarm requiring redress with a corrective action plan. Please see the Negative Float blog for additional discussion.

8. High Duration

The test: A percentage of tasks in the current planning period with baseline durations greater than 44 days. This check excludes LOE, planning packages and summary level planning packages.

The threshold: 5%.

Near term tasks should be broken down to a sufficient level of detail to define the project work and delivery requirements. These tasks should be shorter and more detailed since more is known about the immediate scope and schedule requirements and resource availabilities. For tasks beyond the rolling wave period, longer duration tasks in planning packages are acceptable, as long as the IMS can still be used to accurately develop Driving Paths to Event Milestones and a Program Critical Path to the end of the project.

9. Invalid Dates

The test: Percentage of tasks with actual start or finish dates beyond the Data Date, or without actual start or finish dates before the Data Date.

The threshold: 0%.

The check is designed to ensure activities are statused with respect to the Data Date in the IMS. Claiming actual start or finish dates in the future are not acceptable from a scheduling perspective, but can also create distortions in the EVM System by erroneously claiming Earned Value in the current period for future effort. Alternately, if tasks are not statused with actual start or finish dates prior to the Data Date, then they cannot be logically started or finished until at least the day of the Data Date, if not later. If the forecast dates are not moved to the Data Date or later, the schedule cannot be used to correctly calculate Driving Paths to an Event Milestone, or calculate the Program Critical Path.

10. No Assigned Resources

The test: Percentage of incomplete activities that do not have resources assigned to them.

The threshold: 0%.

This is a complex check because of two basic factors: 1) resources are not required to be loaded on tasks unless directed by the contractor’s internal management requirements, and 2) some tasks such as Schedule Visibility Tasks (SVTs) and Schedule Margin tasks should not be associated with work effort. If the contractor chooses not to load resources into the schedule the options are:

- Associate basic quantities of work with tasks and define in a code field, transfer those quantities to the EVM cost system and verify the traceability between the IMS quantities and the associated budgets in the cost system.

- Maintain the budgets entirely in the EVM cost system and provide a trace point from the activities in the IMS to the associated budgets in the cost system. The trace points are usually in the form of control account and work package/planning package code values.

In either case, care must be exercised so that Schedule Visibility Tasks are reviewed and confirmed to ensure that work is not misrepresented to either the contractor or the customer.

11. Missed Activities

The test: Percentage of completed activities, or activities that should have been completed based on their baseline finish dates, and failed to finish on those dates.

The threshold: 5%.

Many people view this as a performance metric. That is true, but it is also used to review the quality of the baseline. For example, if a project has a 50% failure rate to date, what level of confidence should the customer have in future progress? Is the baseline a workable plan to successfully complete the project? Does the EVM System reflect the same issues as the IMS? If not, are they correctly and directly connected? These are questions that should be addressed by the contractor before the customer or other oversight entities ask them.

12. Critical Path Test

The test: Select a task on the program Critical Path and add a large amount of duration to that task, typically 600 days.

The threshold: The end task or milestone should slip by as many days as the delay in the Critical Path task.

This is a test of the integrity of the schedule tool to correctly calculate a Critical Path. If the end task or milestone does not slip by as many days as the artificial delay, there are structural issues inhibiting this slip. These issues may be logic links, hard constraints or other impediments to the ability of the schedule to reflect the slip. These issues should be addressed and corrected as the schedule data is to be relied upon to provide meaningful information to management.

13. Critical Path Length Index (CPLI)

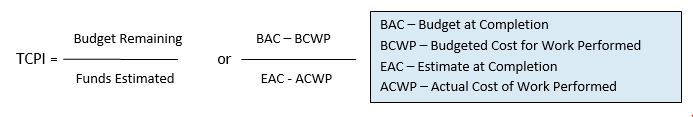

The test: The Critical Path length + the Total Float on the Critical Path divided by the Critical Path Length. This formula provides a ratio that puts the Critical Path Float in perspective with the Critical Path length.

The threshold: .95 or higher.

If the program is running with zero (0) Total Float on the Program Critical Path, then the ratio is 1.00. If there is negative float on the Program Critical Path, then the ratio will fall below 1.00 which indicates that the schedule may not be realistic and that project milestones may not be met.

14. Baseline Execution Index

The test: The number of completed activities divided by the number of activities that should have been completed based upon the baseline finish dates.

The threshold: .95 or higher.

This check measures the efficiency of the performance to the plan. As such, some people also dismiss this as a simple performance metric, but as in the case of Metric #11 (Missed Tasks), this is also a measurement of the realism of the baseline plan. As in Metric #11, if the schedule performance is consistently not to the plan, how viable is the plan? How viable is the EVMS baseline? How accurate is the information from the baseline that Management is using to make key decisions? Metrics #11 and #14 may reflect the result of the effort being performed on the contract, but also represent the quality and realism of the baseline plan.

What are additional metrics that help identify schedule quality issues?

The DCMA’s 14 point schedule assessment should be considered a basic check of a schedule’s health, but by no means is the only check that should be used to analyze an IMS. More industry standard checks are identified in other documents, including the Planning and Scheduling Excellence Guide (PASEG) revision 2.0 (6/22/12). The PASEG is a National Defense Industrial Association (NDIA) product and was developed in cooperation between industry and the Department of Defense. Section 10.4, Schedule Execution Metrics, discusses in greater detail some of the Health Metrics identified above, as well as other metrics including the Current Execution Index (CEI) and the Total Float Consumption Index (TFCI).

In addition to these metrics, checks should be performed on activity descriptions, activity code field values, risk inputs, Earned Value Techniques and other tests to assure alignment of the IMS with its partner information systems. These systems include, but are not limited to the MRP system, the cost system, program finance systems and the risk management system. The IMS in an integral component of a company’s management system, therefore issues with the IMS data will be reflected in the other components of the EVMS.

All of the above health checks can be performed manually with the use of filters and grouping functions within the scheduling tool; however, they may take too much time and effort to be successfully sustained. The marketplace has tools available to perform these and other checks within seconds, saving time and cost, allowing schedule analysts and management to devote valuable time to address and resolve the issues. With the aid of these tools, a comprehensive schedule health check can be performed as part of the business rhythm instead of an occasional, time available basis.

Summary

Schedule Health Metrics are an important component of the schedule development and maintenance process. While the DCMA has established some basic standards for schedule health assessments, the 14 metrics should not be considered the only checks, but just the beginning of the schedule quality process.

Schedule checks should be an integral part of the schedule business rhythm and when issues are identified, they should be addressed quickly and effectively. Significant numbers of tasks that trip the metrics, or persistent issues that are not resolved, may require a Root Cause Analysis (RCA) to identify the reasons for the problems and to develop a plan to address them.

Give Humphreys & Associates a call or send us an email if you have any questions about this article.