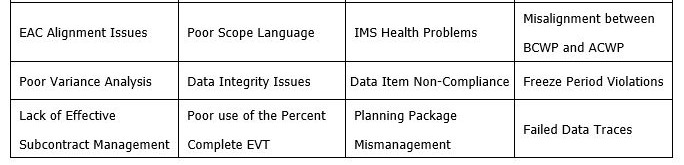

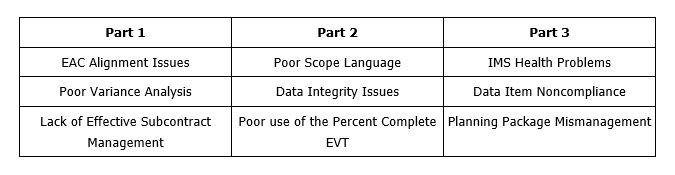

This is the fourth part of a five part series regarding common problems found in EVM Systems and the recommended corrective actions to help mitigate those findings. The previous three articles discussed:

The topics anticipated for part five are: Inappropriate use of PERT and LOE; Misuse of Management Reserve: Administrative CAMs.

1) Misalignment between BCWP and ACWP

The Earned Value Management System Description Document (EVM SDD) should include a statement that requires Actual Cost of Work Performed (ACWP) to be reported within the same accounting period as Budgeted Cost for Work Performed (BCWP) is earned; which is most applicable for material. Both ACWP and BCWP contain the term “Work Performed”. The ACWP is not a measure of how much has been spent but rather reflects how much it cost to accomplish the scope of work reflected in the BCWP.

Accounting systems generally record actual costs for material when invoices are paid; this may or may not align with when earned value is claimed for that material. If material earned value is claimed at point of usage, it may be necessary to collect actual costs in a holding account and then delay recording ACWP in the earned value system until the material is used.

When material earned value is taken at the point of receipt, invoice payments may be delayed for 45 days (or more). The actual costs associated with this material will be recorded in the accounting system after the earned value credit is taken. In this case, recording ACWP in the earned value system must be accelerated. The process of delaying or accelerating the recording of ACWP in the earned value system is often called using “Estimated Actuals” or, more appropriately, “Estimated ACWP”.

There are two obvious examples of this process being done incorrectly. The first is in the data where BCWP is claimed without corresponding ACWP in the current period, or vice versa. This may be below the threshold level for variance explanation and is often attributable to Level of Effort (LOE) control accounts, but it creates a situation that attentive customers will need to understand. The second example is more direct, and occurs when contractors simply explain the situation in Variance Analysis Reports that are subsequently summarized in the Contract Performance Report (CPR) or Integrated Program Management Report (IPMR) Format 5. The Control Account Manager (CAM) will use words such as “billing lag,” “accrual delay,” or “late invoicing” in the explanation of a cost variance. Consequently, any time that financial billing terms are used to explain a cost variance, it raises a flag regarding a potential misalignment between BCWP and ACWP.

One issue with ACWP and BCWP misalignment is that it invalidates the use of the earned value data for predictive purposes. Unless both data elements are recorded within the same accounting period, using indices such as the CPI, TCPI, or IEAC (Independent Estimate at Completion) will deliver erroneous results. The time and effort of the CAMs in the variance analysis process should be spent on managing the physical progress and efficiencies of the work, not having to explain payment or accounting system irregularities.

Most Common Corrective Action Plans

When this issue is reported, the best response is to develop a disciplined Estimated ACWP process, including logs and a monthly trace from the Accounting General Ledger to the EVM ACWP. It is also important to train the CAMs and support staff on how to record and subsequently retire those entries in an Estimated ACWP log book. Reviewers of the Variance Analysis Reports should be trained to screen for entries that indicate an inappropriate alignment between BCWP and ACWP. In addition, as indicated in the blog discussion on Data Integrity (Part 2 of this series), situations where there is BCWP without corresponding ACWP, or vice versa, at the control account level, should be flagged and justified by the CAM prior to submittal of the CPR/IPMR to the customer.

2) Freeze Period Violations

“Freeze Period” refers to future accounting periods, including the current accounting period, in which baseline changes should be strictly controlled. This is also sometimes called the “Change Control Period”. The definition of this period should be in the company’s EVM SDD, but will usually have a time-frame such as “current accounting period plus the next accounting period”. The SDD should specify what kinds of changes are allowed within this period, how they are to be documented in the CPR/IPMR, and any necessary customer notification or approval requirements when these changes are incorporated. The SDD should require that customer approval is necessary for changes to open work packages that affect BCWS or BCWP in the current or prior accounting periods, and any changes to LOE data in prior periods or in the current period if the LOE account has incurred charges (ACWP).

There is an additional requirement specific to retroactive adjustments which includes the current period. The EIA-748-C Guideline 30 specifically stipulates the requirement that these types of changes be controlled, and that adjustments should be made only for “correction of errors, routine account adjustments, effects of customer or management directed changes, or to improve the baseline integrity and accuracy of performance measurement data”. Again, the reasons allowed for the changes should be specified in the EVM SDD. However, regardless of the reason, it is a requirement that all retroactive changes be reflected in the current period data in the CPR/IPMR Formats 1 and 3, and that Format 5 include the related explanations (National Defense Industrial Association (NDIA), Integrated Program Management Division (IPMD), Earned Value Management Systems Intent Guide, August 2012).

Some projects have a great deal of volatility. The incorporation of subcontractor data (especially if that data lags the prime contractor reporting period) and accounting system adjustments often create retroactive (including current period) adjustments. The operation of change boards may also result in changes, both internal and external, which require immediate implementation. EVM compliance in this environment is a matter of disciplined incorporation of changes, including visibility and communication to the customer (and sometimes prior approval) of any impacts to the baseline.

Most Common Corrective Action Plans

When discrepancies are found with freeze period noncompliances, the first action should be to ensure that procedures are in place that are compliant with the EIA-748. The discipline required by these procedures must be communicated to the program team so that a consistent change control processes is maintained. Key to compliance is visibility and communication of freeze period changes via CPR/IPMR Formats 3 and 5.

H&A has seen a loose interpretation of the guideline allowance for adjustments to “improve the baseline integrity and accuracy of performance measurement data”. Care must be taken that adjustments falling under this category are not made to avoid variances.

3) Failed Data Traces

The reviews associated with EVM surveillance and compliance have become increasingly data centric for the past several years. One of the first steps in a review is submittal to the customer of a complete set of EVM data so analysis can be conducted against predefined success criteria prior to conducting an on-site review. When there is an on-site review, the data trace portion of that review can be a major component at the company, project, and Control Account Manager levels.

The primary purpose of the data traces is to evaluate the Earned Value Management System. Is the EVMS operating as a single integrated system that can be counted on for reliable and valid information? The data traces performed generally follow three separate threads: Scope, Schedule, and Budget. There are a variety of documents and reports that contain this information, but the reviewers will look for a single thread of data to flow and be traceable throughout the system.

All systems are different, but a common strategy for data traces might be as follows:

- Scope: WAD → WBS Dictionary → Contract Statement of Work.

- Schedule: WAD → IMS → CAP.

- Cost (Budget): RAM → WAD → IMS → CAP → CPR/IPMR Format 1 → CPR/IPMR Format 5.

- Cost (ACWP): CAP → Internal Reports → CPR/IPMR (Formats 1 & 2) → General Ledger.

If there are also supplemental sources of data that flow into the EVMS, such as subcontractor, manufacturing, or engineering reports, then these should also be a part of the data trace.

The key to this process is the concept of “traceability”. The easiest path to prove traceability is if the data are an exact match; however, this is not always possible. Prime contractors often have to make adjustments to subcontractor data, use of estimated ACWP often will not allow a match with the accounting ledger, and supplemental schedules often “support” the IMS while not matching exactly. These are normal and explainable disconnects in the data. When submitting data for review, it is important to know where the data does not match and to pass that information on to the reviewers. If preparing for an on-site review, the CAMs and others who may be scheduled for discussions should perform a thorough scrub of the data and have quick explanations available when a trace is not evident in that data.

Most Common Corrective Action Plans

It is important that any special circumstances that cause traceability issues be relayed to the review team with the data submittal. The people who conduct the analysis often operate independently until they are on-site for the review, and it is possible to avoid misunderstandings by identifying any issues with the submitted data set. This type of communication has the potential to eliminate unnecessary findings.

A short term response to a data trace issue is to establish a process to screen the EVM data before submission to the customer. Starting with the accounting month end, the statusing and close-out process requires a comparative analysis of the various databases containing the same information. Because of the volume of data contained in most systems, this should be automated. There should be time in the monthly business rhythm to allow for corrections and data reloads to improve the accuracy across the various data locations.

The best approach to improved data traces is to design a system that minimizes the number of entries for a single set of data. For example, H&A found one contractor with over 10 different databases where the CAM’s name was hand entered which resulted in a configuration control nightmare for that data element. The process of system design should include a complete listing of common data elements that are included in the storyboarding of the process flow.

The topics anticipated for Part 5 are: Inappropriate use of PERT and LOE; Misuse of Management Reserve: Administrative CAMs.

To read previous installments:

- Part 1 – EAC Alignment Issues, Poor Variance Analysis, Lack of Effective Subcontract Management

- Part 2 – Poor use of Percent Complete; Data Integrity Issues; Poor Scope Language

- Part 3 – IMS Health Problems; Data Item Non-Compliance; Planning Package Misuse