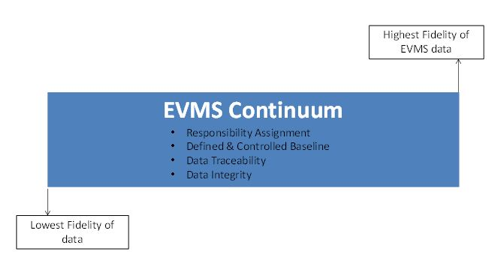

The Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) issued the “7 Principles of Earned Value Management Tier 2 System Implementation Intent Guide,” 21 December 2011. Since most of BARDA acquisitions are unique in that they are not Information Technology (IT) projects or Construction projects, they developed a tiered approach to applying EVMS. Tier 1 are construction and IT contracts and will require full ANSI/EIA-748 compliance. Tier 2 contracts are defined as countermeasure research and development contracts that have a total acquisition cost greater than $25 million and have a Technical Readiness Level of less than 7. Tier 2 contracts will apply EVM principles that comply with the 7 Principles of EVM Implementation. Tier 3 are countermeasure research and development contracts between $10 million and $25 million and will require EVM implementation that is consistent with the 7 Principles approach. The focus of this implementation guide is on the Tier 2 contracts.

The Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) issued the “7 Principles of Earned Value Management Tier 2 System Implementation Intent Guide,” 21 December 2011. Since most of BARDA acquisitions are unique in that they are not Information Technology (IT) projects or Construction projects, they developed a tiered approach to applying EVMS. Tier 1 are construction and IT contracts and will require full ANSI/EIA-748 compliance. Tier 2 contracts are defined as countermeasure research and development contracts that have a total acquisition cost greater than $25 million and have a Technical Readiness Level of less than 7. Tier 2 contracts will apply EVM principles that comply with the 7 Principles of EVM Implementation. Tier 3 are countermeasure research and development contracts between $10 million and $25 million and will require EVM implementation that is consistent with the 7 Principles approach. The focus of this implementation guide is on the Tier 2 contracts.

The Intent Guide contains explanations for each Principle, a Glossary of Terms, a Supplemental EVM Implementation Guideline, and Sample EVM Documents. The Supplemental EVM Implementation Guideline contains recommendations regarding EVM process flows, tools, the necessity to integrate the EVM engine with the accounting system, basic documentation requirements, ranges of implementation costs, recommendations on requirements for support personnel, and use of the 7 Principles on Tier 3 programs.

The Intent Guide defines Tier 2 as: “For countermeasure research and development contracts that have total acquisition costs greater than or equal to $25 million and have a Technical Readiness Level (TRL) of less than 7 will apply EVM principles for tracking cost, schedule and technical performance that comply with the 7 Principles of EVM Implementation.”

The 7 Principles of Earned Value Management

1. Plan all work scope to completion.

This Principle includes development of a Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) and WBS Dictionary that includes all of the work scope. It is also recommended that detailed scope definition be accomplished at the work package level.

2. Break down the program work scope into finite pieces that can be assigned to a responsible person or organization for control of technical, schedule and cost objectives.

This Principle defines the schedule requirements. Most scheduling functions are required including network scheduling, horizontal and vertical traceability, forecasting schedule start and complete dates, and critical path analysis. The contract milestones must also be included in the schedule.

This Principle also discusses the organizational requirements. The Control Account Manager must be identified but there is no requirement for the costs to roll up through organizational elements; this, and development of an Organization Breakdown Structure (OBS) is recommended if it can be done in a cost effective manner.

3. Integrate program work scope, schedule, and cost objectives into a performance measurement baseline plan against which accomplishments can be measured. Control changes to the baseline.

This Principle is discussed in the Intent Guide in two parts. The first, 3a, regards integration of scope, schedule, and cost objectives into a performance measurement baseline. The schedule can be either resource loaded or the budgets loaded into a cost tool and a time-phased control account plan generated. The cost tool must be linked to the schedule tool to ensure baseline integration. The planning includes both direct and indirect dollars.

This Principle also defines the use of undistributed budget and management reserve.

The second part of this Principle, 3b, is the requirement to control changes to the baseline. This requires that contractual changes be incorporated to the baseline in a timely manner.

Budget logs are to be used to track both external and internal changes. All changes are to have documentation that explains the rational/justification for the change and the scope, schedule and budget for that change.

4. Use actual costs incurred and recorded in accomplishing the work performed.

This Principle requires that actual costs be accumulated in a formal accounting system consistent with the way the work was planned and budgeted. A work order or job order coding system must be used to identify costs to the control account and allow summarization through higher levels of the Work Breakdown Structure. The use of estimated actuals is also required for material and subcontractors to ensure that earned value data is not skewed.

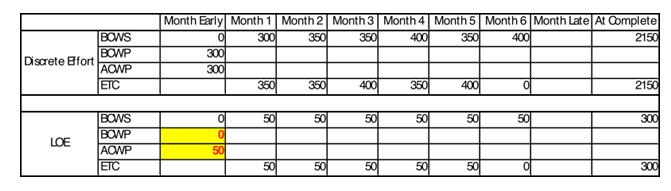

5. Objectively assess accomplishments at the work performance level.

This Principle requires that schedule status and earned value assessment must occur at least monthly. The allowable earned value techniques are discussed as well as the requirements of for the use of each.

6. Analyze significant variances from the plan, forecast impacts, and prepare an estimate at completion based on performance to date and work to be performed.

This principle is also divided into two parts. The first, 6a, regards the analysis of variances from the plan. The earned value system must be able to calculate cost and schedule variances, at least cumulatively, on a monthly basis. The system should also be able to provide the Cost Performance Index (CPI), the Schedule Performance Index (SPI), and the use of the To-Complete Performance Index (TCPI) is also encouraged. Variances that exceed the contract variance thresholds must be explained in terms of the cause, impact and corrective action. Although this Principle does not discuss the preparation of a Variance Analysis Report (<abbr=”Variance Analysis Report”>VAR) by the CAM, Principle 7 does require that Program Managers hold their CAMs accountable to write a proper Variance Analysis Report (Earned Value Management Analysis).

The second part of this Principle, 6b, requires that an Estimate at Completion (EAC) be prepared based on performance to date and the work remaining to be performed.

7. Use earned value information in the company’s management processes.

This Principle regards Program Management use of the earned value data to manage the program’s technical, schedule and cost issues and how that data is used in the decision making process.

Although much of the language in the Intent Guide is similar to that of typical guidance documents for the EVMS requirements, it must be remembered that the EVMS Guidelines are not being implemented, only the 7 Principles. The Principles define an approach to managing programs with the basic requirements of Earned Value; such that the cost of the system is minimized, but only those elements necessary to manage these types of programs are necessary. This allows for further system flexibility and reduces the documentation needed. For instance, in Principle 1, the requirements of the WBS Dictionary could be expanded to contain the information that would normally be included on the Work Authorization Document. If this were done, Work Authorization Documents are not necessary because the WAD content normally contained would be embodied in the WBS dictionary; and the associated cost is reduced over the life of the program.

With the 7 Principles there is no need for an EVM compliance review. An Integrated Baseline Review (IBR), also known as a Performance Measurement Baseline Review (PMBR), could be required.

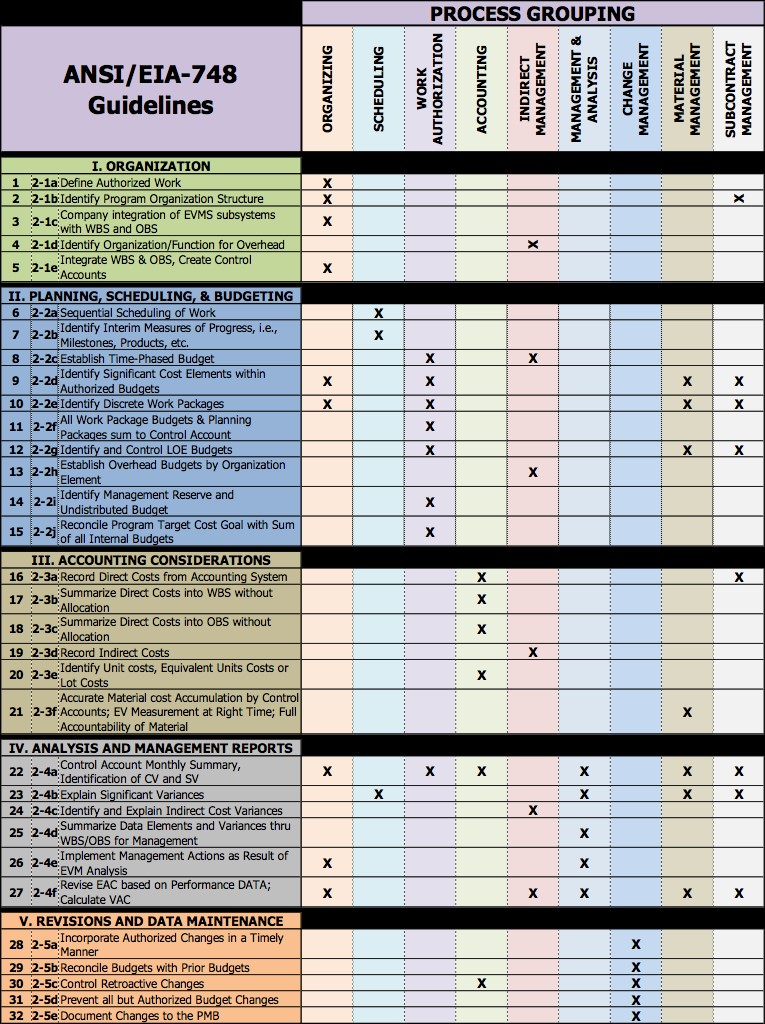

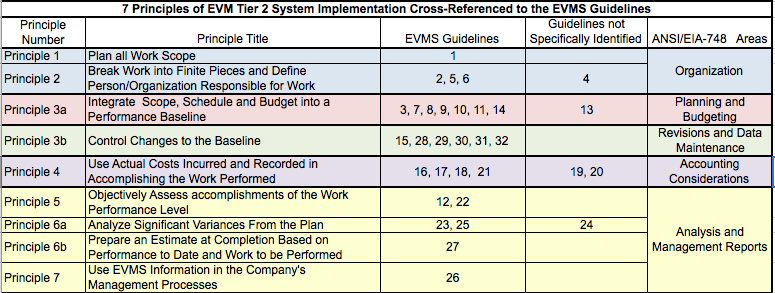

The 7 Principles Comparison to the EIA-748 32 Guidelines

For those who are more accustomed to the EVMS Guidelines as described in the EIA Standard, EIA-748, in the table below the 7 Principles are loosely identified to the 32 Guidelines and Guideline areas. This does not mean that all of the requirements must be met with the 7 Principles only that they can be cross-referenced. Several of the Guidelines are not specifically identified but could be considered as incorporated by reference. The indirect cost requirements are incorporated by planning the work with both direct and indirect dollars; therefore, it is implied that budget, earned value, and actual costs would also include both direct and indirect costs.

The appendix also contains the requirement that the EVM Engine needs to be integrated with the company’s accounting system. Further, some programs may also be required to be compliant with the Cost Accounting Standards. Guideline 20, “Identify unit costs, equivalent units costs, or lot costs when needed” is not included; this more than likely would not be a requirement for HHS or BARDA programs.

|

|

|

|

|

| 7 Principles of EVM Tier 2 System Implementation Cross-Reference to the EVMS Guidelines |

| Principle Number |

Principle Title |

EVMS Guidelines |

Guidelines not Specifically Indentified |

ANSI/EIA-748 Areas |

| Principle 1 |

Plan all Work Scope |

1 |

|

Organization |

| Principle 2 |

Break Work into Finite Pieces and Define Person/Organization Responsible for Work |

2, 5, 6 |

4 |

|

Principle 3a

|

Integrate Scope, Schedule and Budget into a Performance Baseline |

3, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 14 |

13 |

Planning & Budgeting |

|

Principle 3b

|

Control Changes to the Baseline |

15, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 |

|

Revision & Data Maintenance |

| Principle 4 |

Use Actual Costs Incurred and Recorded in Accomplishing the Work Performed |

16, 17, 18, 21 |

19, 20 |

Accounting Considerations |

| Principle 5 |

Objectively Assess Accomplishments of the Work Performance “Level |

12, 22 |

|

EVM Analysis & Management Reports |

|

Principle 6a

|

Analyze Significant Variances fomr the Plan |

23, 25 |

24 |

|

Principle 6b

|

Prepare and Estimate at Completion based on Performance to-data and Workd to be Performed |

27 |

|

| Principle 7 |

Use EVM information in the Company’s Management Processes |

26 |

|

Recommendations for Enhancement to the Intent Guide

The 7 Principles Intent Guide was issued in December 2011. In June 2012 the requirements for the Integrated Program Management Report (IPMR) was issued; this will replace the Contract Performance Report (CPR) for contracts issued after June 2012. When a revision to the Intent Guide is issued, the IPMR should be included.

The Intent Guide is a “what to do” document and contains little on “how to do it”. Internal procedural documents should be required to define how a company will implement the Guide requirements.

Principle 6a requires that the cost and schedule variances be calculated at least on a cumulative basis and only recommends calculation of the current month. The current month calculation should be a requirement since both the CPR and the IPMR require current month reporting.

Summary

The “7 Principles of Tier 2 System Implementation Intent Guide” requires the basic elements of earned value and the documentation necessary to demonstrate that earned value is being adequately implemented on Tier 2 programs. H&A personnel understand the requirements and are able to “size” those requirements to meet company and customer needs. Click to request a PDF copy of the Intent Guide.

Humphreys & Associates (H&A) has been providing Earned Value Management training and implementation services for over 35 years. H&A provides self-paced online, classroom and private training courses, as well as training tailored to specific industry needs, and can assist in all aspects of Earned Value Management Implementation.

For more information about EVM training or support, or with questions about your company’s requirements, please contact the Humphreys & Associates corporate office.