Rolling Wave Planning for Earned Value Management Systems

If someone were to ask you: “Can you please give me a detailed explanation of what you will be doing on this date three years from now?” you would probably look at that person as though he or she were crazy. It would probably be difficult to provide a detailed schedule of events for a date one week from now – although that might be more likely since you know a lot more about what might be taking place next week than what might be happening three years out.

In the early days of earned value management, contractors were expected to detail plan the entire length of a program to establish a “good performance measurement baseline.” For a year-long development program this expectation might be okay, but for a 10 to 12 year shipbuilding program it might be unreasonable and probably a monumental waste of time. The program will no doubt change several times before its completion – maybe several times in the first year alone. With industry’s “help” the government soon realized requiring detail plans on lengthy programs was not always possible – or even meaningful – especially when program requirements are often fluid.

The government and industry agreed that contractors could provide an overall (general, straight-line, “average”, etc.) plan for accomplishing a program very much like what is already done in preparing a proposal, and then provide more details on an incremental basis as more became known about the work to be performed. The government is not keen on having contractors do detail planning whenever they felt the urge, so they sought to put reasonable rigor into the incremental planning process. All the work that existed beyond the detail planned work was considered by the government to be general “planning packages”, although contractors were still permitted to detail plan as much of the future work as they wanted.

The government also expected the contractors to identify the planning increments and frequency of planning to ensure there was not a time when the detail planned work was completed and there was no more future work detail planned. The expectation soon became that contractors were to expand a detail plan from those planning packages into detail planned work packages with enough frequency to ensure there was always a minimum number of months of detail plans in place when the next detail planning event took place. It also became evident that more months of detail (often called a “planning horizon”) could be provided on production or manufacturing type work vs. for development type effort.

As this “straight-line” plan was converted into detailed work package plans, the straight line became more curved (such as bell curve or skewed bell curves), with more “waves” rolling in as it became time to detail plan. This type of planning became known as “rolling wave planning”. Some companies call their process “incremental”, “accordion”, or “inchworm” planning process – the name does not matter, so long as the application of the process results in a minimum amount of detail planned work packages always being in place on a program.

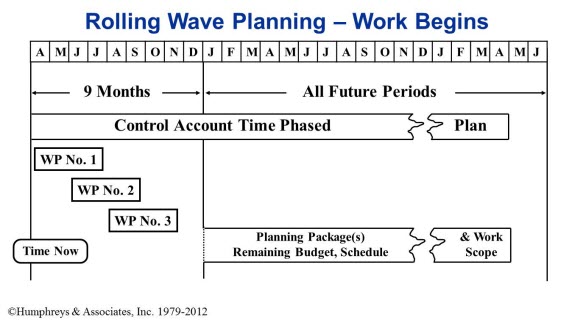

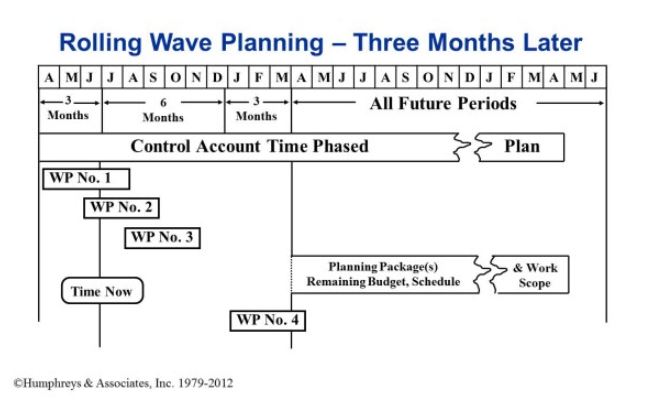

A production program might have, for example, a 9 month planning horizon with a quarterly frequency. In this scenario, the program starts with 9 months of detail planning in place. Three months later, the Control Account Manager (CAM) is to look at the next 9 months (6 already detail planned and 3 new months) to make sure the existing detail planning is still good and to plan out in detail those new tasks that should be starting in the new three months of the planning horizon.

A development program however, is likely to use a different planning horizon. Because of program volatility, it often has a shorter horizon and a higher frequency, such as 4 months of detail planning in place, with a one or two month frequency.

An example for a production program is illustrated below. The program manager determines production can do detail planning for nine months and then every quarter review the next nine months for:

- New work scheduled to commence in the next three months of the planning horizon and

- Five of the six months already detail planned in the prior incremental assessment (depending on the company’s “freeze period”) – WP No. 3 and beyond can be re-planned

Rolling Wave Planning for long term projects is a common area where control account project managers need help. Humphreys & Associates earned value management experts can provide the guidance you need for your unique production or development project. Contact us for more information.

Rolling Wave Planning for Earned Value Management Systems Read Post »