What is the Difference Between Budget and Funds?

Quick Summary

- A budget is a project management metric used to plan and measure performance, while funds are real dollars recorded in the accounting system and spent to perform the work.

- Earned Value Management distinguishes planned values (e.g., BCWS, BCWP, BAC) from actual costs and estimates (e.g., ACWP, ETC, EAC) to provide insight into project performance and funding needs.

- Contract funding profiles influence how budgets are time-phased, and regular EAC analysis is essential to forecast total funding requirements and avoid breaching funding limits.

While working with numerous clients over the years, H&A earned value consultants frequently observe people using the term “money.” Typically, they mean “funds” when they really mean “budget.” People often confuse the terms, even though they have been used within the project management community long before the advent of earned value management practices.

The intention of this blog is to highlight the difference between “budget” and “funds” and promote a common understanding of the terms. Using the correct term helps to eliminate confusion and improve communication between project team members, management, and the customer.

Examples of Budget and Funds Confusion

Here are a couple of common statements H&A earned value consultants have heard many times:

- I am requesting management reserve (MR) to fund my overrun.

- I underran my budget, so I am going to return funds to MR.

Why are these inaccurate statements? The people making them have confused the terms or may think that “budget” and “funds” mean the same thing.

Explaining the Difference Between Budget and Funds

The simple definition is that “budget” is a project management metric, a planned value. It cannot be used as funds (i.e., money) to buy something tangible, such as a cup of coffee. “Funds” are real dollars. The purpose for budget is to measure project performance so that as funds are expended (the actual costs) to perform the authorized work, any difference, more or less than what was planned, can alert management.

The table below summarizes the differences between the two terms.

| Budget | Funds |

|---|---|

| Cannot be spent | Money – real dollars being spent or forecasted to be spent. Funding represents the customer’s ability and commitment to pay. |

| A number on a piece of paper, in a spreadsheet or database – it is a project management metric | Actual costs recorded in the accounting system of record used for financial reporting |

Budgeted Cost for Work Scheduled (BCWS)

|

Estimate to Complete (ETC)

|

Budgeted Cost for Work Performed (BCWP)

|

Actual Cost of Work Performed (ACWP)

|

Budget at Completion (BAC)

|

Estimate at Completion (EAC)

|

An Overview of Budget Terms

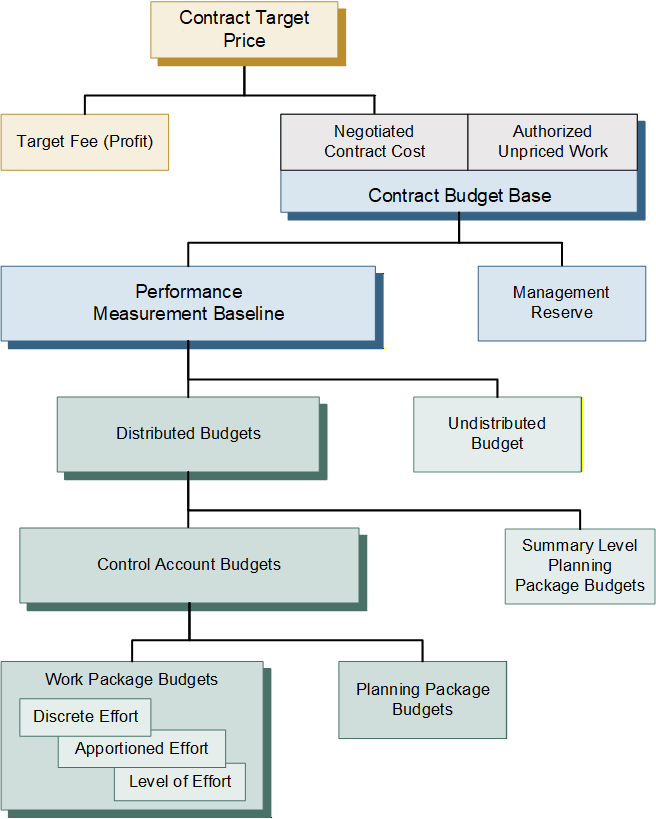

It is often helpful to review the basis for determining and distributing a project’s total budget used for planning and measuring project performance, as illustrated in Figure 1. Note: this is a simplified discussion to highlight the budget terms and does not include nuances such as an Over Target Baseline (OTB) situation.

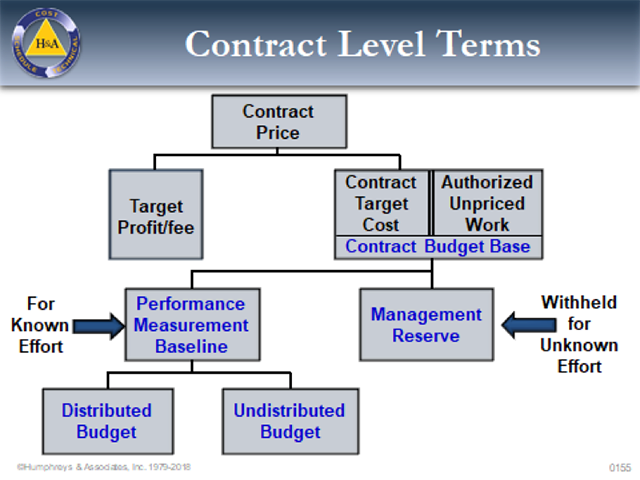

The budgeting process begins with the Contract Target Price (CTP). This is the total negotiated contract value. It includes the negotiated contract cost (NCC) plus the contractor’s planned (target) profit or fee. The Contract Budget Base (CBB) is the starting point for a contractor’s internal budgeting process outlined below.

| Budget Component | Definition |

|---|---|

| Contract Budget Base (CBB) | Represents the financial authorization of the contract and is based on the negotiated contract cost (i.e., price less fee). The CBB is always equal to the negotiated cost for definitized work and the estimated cost for all authorized unpriced work (AUW), also known as Undefinitized Contact Action (UCA). The CBB equals the sum of distributed budgets, undistributed budget, and management reserve (MR). It also equals the sum of the performance measurement baseline (PMB) and MR. |

| Management Reserve (MR) | Amount of contract budget set aside to handle realized risks and emerging in-scope effort. This effort is in scope to the contract, but out of the scope of distributed and undistributed budget. |

| Performance Measurement Baseline (PMB) | The PMB is the sum of all distributed direct and indirect budgets against which contract performance is measured. The PMB is the sum of the distributed budgets and undistributed budget. The PMB plus MR is equal to the CBB. |

| Undistributed Budget (UB) | Budget for authorized work scope that has not yet been identified to a specific WBS element and/or responsible organization at or below the lowest level of reporting to the customer. |

| Distributed Budgets | Distributed budgets may be comprised of summary level planning package (SLPP) and control account budgets. |

| Summary Level Planning Package (SLPP) Budgets | Budget may be set aside in SLPPs at the lowest WBS element until the future work effort can be defined in more detail. SLPPs have a high-level scope of work and are scheduled in the IMS with time-phased budgets. They are converted to one or more control accounts with subordinate work packages and planning packages as soon as possible. |

| Control Account Budgets | Control accounts have a defined scope of work, scheduled start and finish dates, and time-phased budget that reflects the work decomposed to the work package or planning package level. The sum of the time-phased work package and planning package budgets equals the total control account budget. |

| Work Package/Planning Package Budgets | Work packages and planning packages have a defined scope of work, scheduled start and finish date, and time-phased budget based on the parent control account. This lowest level of budget includes the element of cost detail (labor, material, subcontract, and other direct costs) and value detail (hours, units/quantities, direct costs, and indirect costs). |

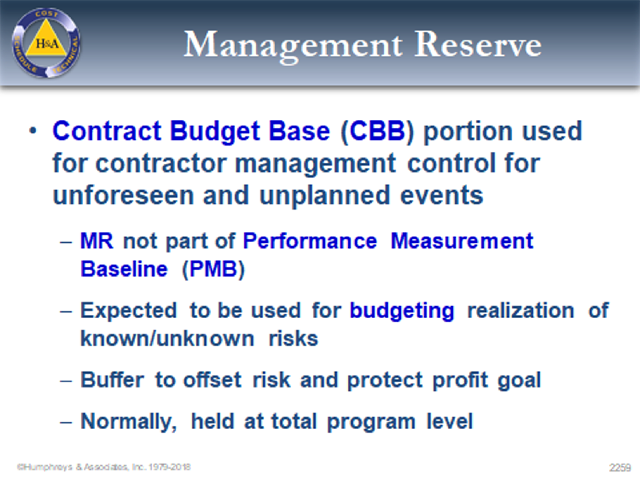

Notes about Management Reserve

Remember that MR is a budget, is not a financial reserve (i.e., a source of funds). It is not time-phased and is not included in the PMB because there is no related work scope, although it is a part of the CBB. MR budget cannot be used to eliminate cost variances, cover cost overruns, or recover underruns. There is only one MR set aside for a project and the value is never negative.

MR is decreased to provide budget for realized risks or unplanned activities within the contract scope of work. It may be increased whenever the work scope is decreased along with the allocated budget (a contract modification). Customer authorized contract changes, including AUW, should be incorporated into the CBB and PMB as soon as possible; this may include MR budget set aside for added work scope. Only contract changes authorized by the customer’s designated contracting officer may change the CBB value.

For more discussion on MR, see this blog: Management Reserve Best Practice Tips. Also see this article: The Difference Between Undistributed Budget and Management Reserve.

Additional note. The MR budget belongs to the contractor’s program manager, not the government customer. MR is not a cost reserve (contingency) for the government customer and may neither be eliminated from contract prices by the customer during subsequent negotiations nor used to absorb the cost of contract changes. For the government customer, contingency is the cost reserve they own, typically associated with a Program Risk-Adjusted Budget (PRB). It is held outside of the project scope, schedule, and budget already provided to the contractor. Reserves held above the program permit senior government management to balance resources within portfolios and among programs. The government customer’s cost reserve could be used to modify the contract to include additional work scope (increases the contractor’s CBB) or provide the funds needed to cover a contract cost overrun.

Budget, Estimates, and Funding Profiles

Contract funding also influences how the PMB budget is allocated and time-phased. The budget distributions are a result of the project planning process (scope of work definition, detailed schedule development, initial cost estimates), MR set aside (risk and opportunity planning), and the funding profile. This is an iterative process to develop the baseline schedule and time-phased budget plan. The budget distributed to the control accounts and any SLPPs is compared to the total PMB/UB value. As needed, adjustments to activities, sequence of work, or resource assignments are made to ensure the overall budget plan reflects the budget limit for the PMB and the contract’s funding profile. For a real-world example of this, see this blog, Understanding the ALAP Scheduling Option in Practical Terms, where a front-loaded schedule was exceeding the funding cap, and how a H&A scheduling consultant helped resolve the issue.

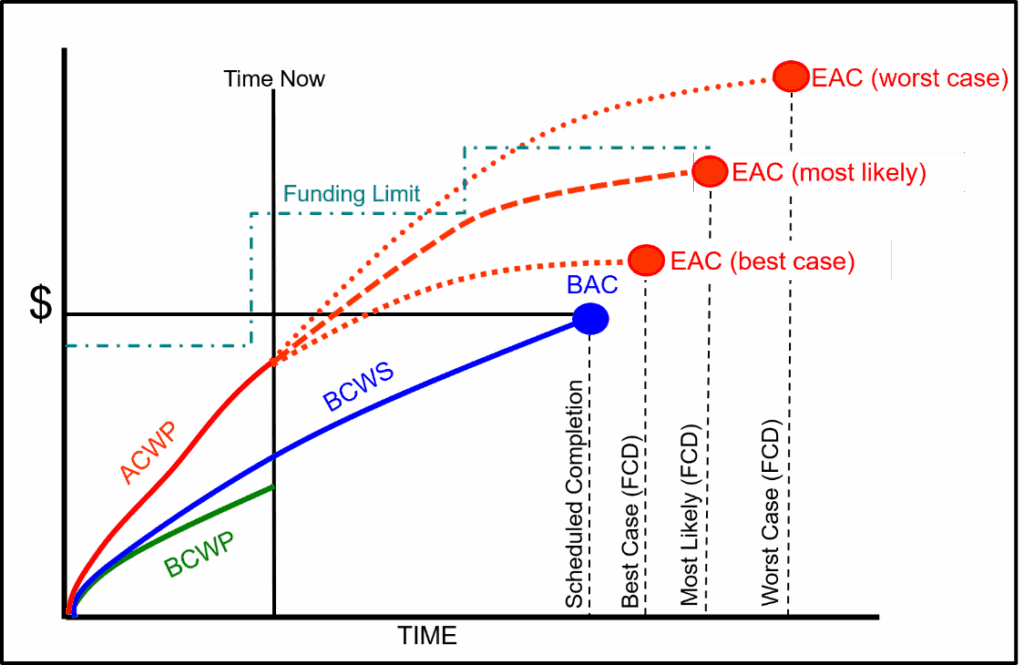

Preparing an EAC every reporting cycle provides an accurate projection of cost at contract completion for internal and external management. It also represents the estimate of total funds required for the contract. The most likely EAC should be within the funding constraints for the contract. Any amounts expended in excess of the contract funding limit puts the contractor at risk. The contractor must notify the customer when their EAC analysis determines there is a potential to breach a funding constraint to address any contract funding issues as quickly as possible.

Figure 2 illustrates a funding profile along with the range of project EACs. In this figure, the most likely EAC is within the contract funding limit.

Reinforcing a Commitment to EVMS Excellence

A common theme of the H&A blogs and articles is helping clients to achieve and maintain a commitment to a high level of excellence in all EVMS process areas. An important part of this is continuous EVM training and project scheduling training, whether for beginners or advanced practitioners. This includes targeted training when clients identify an area where project personnel could use a refresher, more hands-on training, or mentoring. Examples include basic and advanced EVMS workshops, Completing Variance Analysis Reports, Developing an ETC and EAC, as well as short, targeted courses on topics such as Budget versus Funds. Give us a call today at (714) 685-1730 to get started.

What is the Difference Between Budget and Funds? Read Post »