Earned Value Management for Biotech and Pharma – Part 2 Accounting

By Ric Brock – Engagement Director, Humphreys & Associates

As a follow up to our article on the Earned Value Management for Biotech and Pharma Industries, this is a quick look at how Biotech and Pharma companies collect and manage costs compared to accounting requirements on federal acquisitions.

The Operating Model for the Biotech and Pharma Industry

The basis of the Biotech and Pharmaceutical operating model is to discover/invent a compound or device to meet a need, validate its safety and efficacy, ensure proper patent protection, market it as quickly as possible, and maximize commercialization while there is still patent protection. In short, it is about speed to market and maximizing the commercial life cycle.

Operating costs are collected and managed from a process costing basis. Internal costs are usually not collected by a cost objective, as they are not managed to that level of detail. Most internal labor is collected by department total headcount and labor dollars. Project or activity based timekeeping is not practiced; i.e. time cards are not used. External costs (materials, contract services, subcontractors, etc.) are collected within the purchasing system and can be tied to specific activities and traced to the originating departments. Most companies do have the ability to set up and track job costs within their capital management system.

Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR), Cost Accounting Standards (CAS), and Timekeeping

The ability to plan and collect actual costs in a consistent and systematic manner by contract/project is a key to the Earned Value Management System requirement. The costing of items and services purchased by the US Government on a non-firm fixed price basis are covered in the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR) and the Cost Accounting Standards (CAS). The ability to collect costs in a consistent and timely manner is an EVMS prerequisite.

Federal Acquisition Regulations

Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR) are a set of regulations governing the US Government processes of purchasing goods and services. Among the guiding principles are to have an acquisition system that satisfies the customer’s needs in terms of cost, quality, and timeliness; to conduct business with integrity, fairness, and openness; and to fulfill other public policy objectives.

Part 52 of the FAR contains standard contract clauses and solicitation provisions. Many clauses incorporate parts of the FAR into government contracts by reference, thereby imposing FAR rules on contractors.

Part 30 of the FAR describes policies and procedures for applying the Cost Accounting Standards Board (CASB) rules and regulations [48 CFR Chapter 99 (FAR Appendix)] to negotiated contracts and subcontracts. This part does not apply to sealed bid contracts or to any contract with a small business concern [see 48 CFR 9903.201-1(b) (FAR Appendix) for these and other exemptions]. Part 30 also identifies the standard contract clauses and solicitation provisions contained in FAR Part 52 that are to be incorporated when applying the CASB rules and regulations to a contract or subcontract.

When a government agency issues a contract or request for proposal, it will specify a list of FAR clauses that will apply. In order to be awarded the contract, a bidder must either comply with the clauses, demonstrate that it will be able to comply at time of award, and/or claim an exemption from them. A bidder must also ensure that it understands the contractual commitments, as complying with some FAR clauses may require changes to operating processes.

Cost Accounting Standards

Cost Accounting Standards (CAS) are a set of 19 standards and rules (CAS 401 – 420) that the US Government uses in determining the costs on negotiated procurements.

A company may be subject to full CAS coverage (required to follow all 19 standards), modified CAS coverage (required to follow only Standards 401, 402, 405, and 406), or be exempt from coverage.

Full coverage applies only when a company receives either one CAS-covered contract of $50 million or more, or a number of smaller CAS covered contracts totaling $50 million. In addition to complying with the standards, the company must also file a CAS Disclosure Statement (CASB DS-1) which clearly describes the company’s accounting practices (such as what costs are treated as direct contract charges and what costs are treated as part of an overhead expense). There are two versions of the CAS Disclosure Statement: DS-1 applies to commercial companies while DS-2 applies to educational institutions.

Modified coverage applies when a company receives a single contract of $7.5 million or more.

Timekeeping

Despite the significant role timekeeping plays in government contracting, the FAR provides little direction on timekeeping. This lack of guidance has been left to government audit agencies (such as the Defense Contract Audit Agency (DCAA) to establish audit standards. The DCAA uses its Contract Audit Manual (CAM) to provide audit guidance to its auditors. The CAM provides guidance on auditing timekeeping procedures in section 5-909. The audit manual states that timekeeping procedures should be able to “assure that labor hours are accurately recorded and that any corrections to timekeeping records are documented…”.

This timekeeping system should feed a labor distribution system that maintains labor hours and dollars by employee, by project/contract, and type of effort account. This labor distribution should be reconciled to the general ledger labor accounts at least monthly.

Timekeeping is critical. Unlike other contract costs, labor charges are not supported by external documentation. The move by a Biotech/Pharma company to a formal timekeeping system may require extensive cultural change.

Summary

As Biotech and Pharmaceutical companies move to FAR contracting, it will require a transition to a project/job costing basis from a process costing basis. This change may appear straight forward, but any process change requires sound change management.

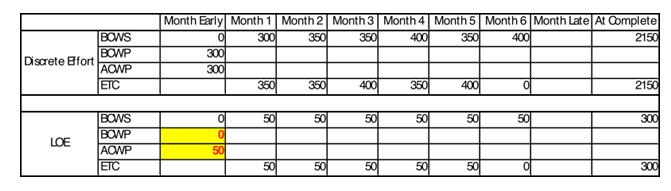

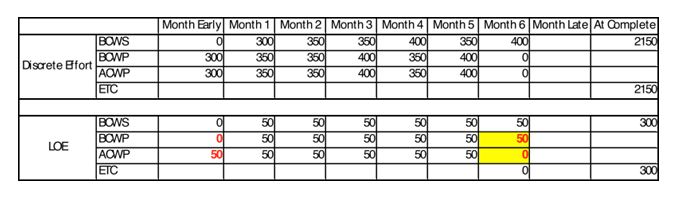

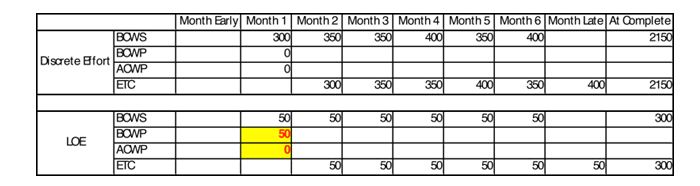

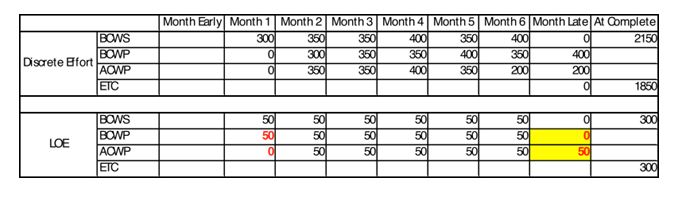

All aspects of EVMS are critical to ensure the utility of an effective program management tool. In this blog we provided a summary level look at cost accounting data. The ability to collect valid, timely, and auditable cost is the foundation for the Actual Cost of Work Performed (ACWP). Without knowing what we accomplished and what we spent to get to where we are, it is very hard to predict where we are going: the Estimate to Complete (ETC). As a company designs and develops its EVMS, it must make sure actual cost collection and management is also addressed within the FAR and CAS requirements.

For questions or inquires on how to implement Earn Value project management in the biotechnology or pharmaceutical industries, contact one of the experts at Humphreys & Associates.

Mr. Brock has over 30 years of experience in program and project management, operations, and quality assurance in government and commercial environments. He has extensive experience working with all levels of an organization, from top management to performing personnel. Ric has extensive experience supporting Pharmaceutical companies in life cycle management, filing new drug applications, and launching new drugs. He has a wealth of experience with EVM systems across a variety of industries from defense to commercial including biotech/pharma. You can find Ric on LinkedIn

Mr. Brock has over 30 years of experience in program and project management, operations, and quality assurance in government and commercial environments. He has extensive experience working with all levels of an organization, from top management to performing personnel. Ric has extensive experience supporting Pharmaceutical companies in life cycle management, filing new drug applications, and launching new drugs. He has a wealth of experience with EVM systems across a variety of industries from defense to commercial including biotech/pharma. You can find Ric on LinkedIn

Earned Value Management for Biotech and Pharma – Part 2 Accounting Read Post »