DOE EVMS Videos: Earned Value Management Systems (EVMS) Training Video Snippets

As part of Department of Energy’s (DOE) Office of Project Management’s (OAPM) continuing efforts to further enhance both communication and instruction among DOE and its Earned Value (EVM) Management contractors and EVMS project managers regarding EVMS requirements, OAPM contracted with Humphreys & Associates (H&A) to develop Earned Value Management Systems (EVMS) training videos. These videos, referred to as Snippets, are available as DOE EVMS training resources within the website of the Energy Facility Contractors Group (EFCOG), in a section dedicated to EVMS Training Snippets.

More about OAPM’s mission, from DOE:

“The Office of Acquisition and Project Management (OAPM) is responsible for all contracting, financial assistance and related activities to fulfill the Department’s multitude of missions through its business relationships. As the business organization of the Department, OAPM develops and supports the policies, procedures and procurement operational elements.”

The EVMS Training Snippets:

- 1.1 DOE O 413.3B EVM Requirements

- 1.2 DOE EVMS Review Approach

- 1.3 EVMS Stage 1 Surveillance

- 1.4 EVMS Stage 2 Surveillance

- 1.5 EVMS Stage 3 Surveillance

- 1.6 DOE EVMS Review for Cause

- 1.7 DOE EVMS Certification

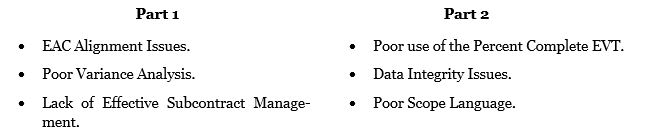

- 1.8 DOE Common EVMS Findings

- 2.1 Contract Performance Report (CPR) / Integrated Program Management Report (IPMR): Purpose and Uses

- 2.2 Contract Performance Report / Integrated Program Management Report: FPD Quick Check

- 2.3 The Integrated Program Management Report (IPMR) Data Item Description

- 2.4 Contract Funds Status Report (CFSR) Overview and Reconciliation with IPMR/CPR

- 3.1A Integrated Master Schedule (IMS) Initial Baseline Review

- 3.1B IMS Monthly Review

- 3.2 Schedule Health Metrics

- 3.3 Schedule Guidance & Resources

- 4.1 OTB OTS Implementation 20140723

- 4.2 Integrated Baseline Review Process

- 4.3 Management Reserve vs. Contingency

- 4.4 Undistributed Budget

- 4.5 Authorized Unpriced Work

- 4.6 Baseline Control Methods

- 4.7 FFP Subcontracting and Prime EVM

- 4.8 Control Account Manager Roles and Surveillance

- 4.9 High Level EVM Expectations

- 5.1 PARSII Overview

- 5.2 PARS II Analysis-Data Validity Report

- 5.3 PARSII Analysis Schedule Health Assessment

- 5.4 PARS II Analysis-Variance Analysis Reports

- 5.5 PARS II Analysis-Trends Reports

- 5.6 PARS II Analysis-EAC Reasonableness & IEACs

- 5.7 PARS II Analysis-OAPM Monthly Report

- 6.1 Predictive Analysis

- 6.2 Applied Predictive Analysis

Additionally, the DOE has provided Project Management Policy and Guidance, Orders and Guides, Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) and Handbooks, Secretarial Memoranda regarding Project Management, Capital Asset Budget Guidance, & Capital Asset Plans within Energy.Gov. Additional information here.

DOE EVMS Videos: Earned Value Management Systems (EVMS) Training Video Snippets Read Post »