Have you been in a meeting when presenters show differing To-Complete Performance Index (TCPI) values at the total contract level for the same contract? In these situations, the presenters have made different assumptions about the inclusion of Undistributed Budget and Management Reserve (MR) in the TCPI calculations. So let’s use some sample values and show different ways the TCPI can be calculated at the total contract level.

Have you been in a meeting when presenters show differing To-Complete Performance Index (TCPI) values at the total contract level for the same contract? In these situations, the presenters have made different assumptions about the inclusion of Undistributed Budget and Management Reserve (MR) in the TCPI calculations. So let’s use some sample values and show different ways the TCPI can be calculated at the total contract level.

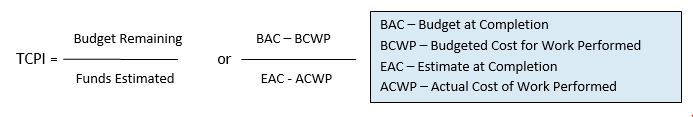

As a reminder, this is the formula for TCPI:

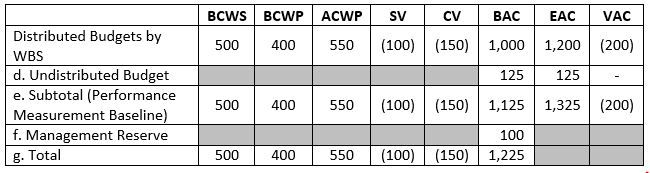

Consider the following extract from the lower right portion of Format 1 of the Integrated Program Management Report (IPMR) (Contract Performance Report (CPR)).

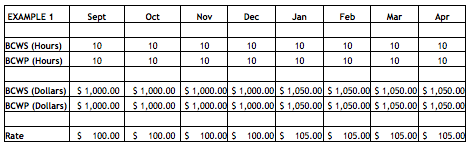

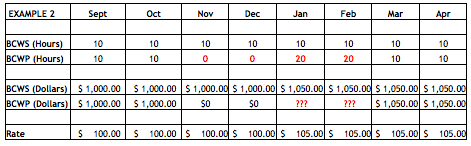

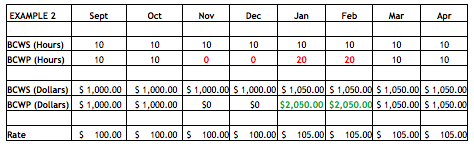

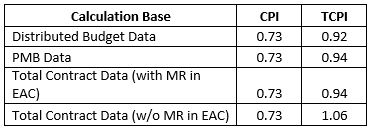

When comparing the TCPI to the CPI at the total contract level, the most realistic approach is to calculate the TCPI at the level of the Distributed Budgets. Stated differently, the TCPI should be calculated without Undistributed Budget and Management Reserve. The Cost Performance Index (CPI), BCWP divided by ACWP, represents the cost efficiency for the work performed to date. Notice in the above table that the BCWP and ACWP values in the rows for “Distributed Budgets by WBS”, “Subtotal”, and “Total” are the same; therefore, the CPI calculation will be the same for any of these data levels. The TCPI represents the cost efficiency necessary to achieve the reported EAC. The “Distributed Budgets by WBS” contain approved budgets as well as performance data against those budgets. The CPI and TCPI compared at this level of data certainly provide a valid comparison of past performance to projected performance. The CPI for the above data is 0.73 while the TCPI is .92.

Since the difference between the CPI and TCPI is greater than 0.10, the control account managers (CAMs) and the analysts should research the reasons that the future performance indicates improvement and provide EAC rationale.

Calculating the TCPI at the Performance Measurement Baseline level (i.e. including Undistributed Budget in the BAC and EAC) yields a different TCPI than at the Distributed Budget level. Mathemati-cally, the TCPI will be the same for the Distributed Budgets and PMB only if the value of the Estimate to Complete (EAC – ACWP) equals the budgeted value of the remaining work (BAC – BCWP). In that case, the TCPI will be 1.0. If the contract has an unfavorable cost variance and projects an overrun on future work, the TCPI at the PMB level (includes UB) will be higher than the TCPI calculated at the Distributed Budget level (does not include UB).

For the data in the above table, the Distributed Budget TCPI = 0.92 but increases to 0.94 if Undistributed Budget is included in the calculation. The Undistributed Budget, with the same value added to both BAC and EAC, represents a portion of the Estimate to Complete (ETC) that will be performed at an efficiency of 1.0. In an overrun situation at the distributed budget level, the disparity between the CPI and TCPI increases when Undistributed Budget is included in the TCPI because more work must be accomplished at a better efficiency to achieve the EAC. In the above data, the disparity between CPI and TCPI increased from 0.19 to 0.21.

Calculating the TCPI at the total contract level with Undistributed Budget and Management Reserve in both the BAC and EAC yields TCPI values very close to TCPI values calculated at the distributed PMB level. The UB and MR values included in the BAC and EAC increase the proportion of the remain-ing work that is forecast to be completed at an efficiency of 1.0 and push the TCPI toward the 1.0 val-ue. The larger the values of UB and MR, the more the TCPI will diverge from the TCPI calculated at the Distributed Budgets level. Using this approach for the sample data above, the CPI is 0.73 and the TCPI is 0.94.

Calculating the TCPI at the total contract level, but not including Management Reserve in the EAC, creates a significant disparity between the CPI and TCPI. This situation represents the classic “apples to oranges” comparison: the work remaining in the formula includes MR, but the funds estimated do not. Obviously, with a higher numerator, the TCPI would be higher than any of the other approaches discussed above. Using this approach for the sample data above, the CPI is 0.73 and the TCPI is 1.06. While situations arise where exclusion of MR from the EAC makes sense, it is still important to review the project manager’s rationale with respect to MR application. Most situations assume that MR will be depleted during contract performance; consequently, it should be added to the EAC at the PMB level.

In summary, be sure you understand what is included in the TCPI calculation before you make comparisons to the CPI at the total contract level. The following table summarizes the CPI and TCPI for the sample data in this article and highlights the differences in the TCPI when calculated at the various data summary levels.

To ask about this topic or if you have questions, feel free to contact Humphreys & Associates.