Common Problems Found in EVMS and Recommended Corrective Actions – Part 5

This is the last of a five part series regarding common findings discovered in contractors’ Earned Value Management Systems (EVMS), and the recommended corrective actions to mitigate those findings.

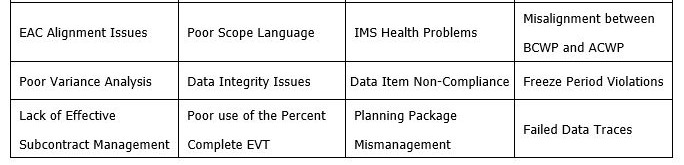

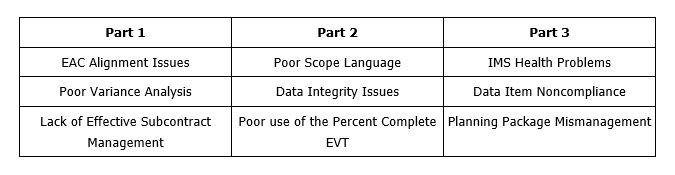

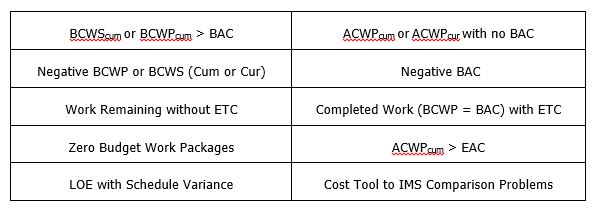

The previous articles discussed:

Part 5 of this series includes: Inappropriate use of PERT and LOE; Misuse of Management Reserve; Administrative Control Account Managers.

1) Inappropriate use of PERT and LOE

The Program Evaluation and Review Technique (PERT) earned value method is a simple method for calculating the BCWP, where: BCWP = (ACWP/EAC) X BAC. In this method, the earned value is completely contingent upon cumulative expenditures (ACWP) divided by an estimate of total expenditures. Because the results of this formula often have little to do with actual progress, its use is limited to non-critical work, and generally is applied only to high volume, low dollar fixed price material. The PERT method should never be used for any critical path task, labor, or high dollar value material. Guideline 7 of the EIA-748-C Standard requires that an EVMS “Identify physical products, milestones, technical performance goals, or other indicators that will be used to measure performance”. The primary condition that must be satisfied in a review of earned value techniques is the application of “meaningful indicators” for use in measuring the status of cost and schedule performance.

Level of effort (LOE) tasks consist of management or sustaining type activities that have no identifiable end products or an established relationship to other measurable effort. The standard for the control of LOE is documented in Guideline 12, which requires that “Only that effort which is immeasurable or for which measurement is impractical may be classified as level of effort”. There is no standard threshold for a contract or WBS level that would signify “too much” LOE. However, a common practice during review discussions with the control account managers is to challenge any LOE to assess its appropriateness. There is always pressure on a contractor to minimize the LOE as the nature of LOE can easily mask or distort the performance of discrete work.

Most Common Corrective Action Plans

The most common response to findings regarding both PERT and LOE is to establish a screening/approval process, with thresholds, during the budgeting process. For PERT, most Earned Value Management System Description Documents (EVM SDD) will specify the limited use of the technique for high volume, low dollar fixed price material. Many also take the next step and create a threshold for what is considered “low dollar” and short duration. This is dependent on the nature of the work, but it is not unusual for an SDD to require that any material extended value (quantity of parts times budgeted unit value) or part number greater than $10,000 (or some other threshold) must be tracked discretely in the IMS and may not use the PERT method. Some also establish a a duration threshold like no greater than 3 months when there are many parts of low value. One of the signs that PERT is being used inappropriately is when variance analysis included in the Integrated Program Management Report (IPMR) or Contract Performance Report (CPR) Format 5 consistently refers to PERT accounts as drivers, or a schedule variance explanation that refers to material not being tracked in the IMS.

Level of Effort should be justified on a case-by-case basis. A common strategy for setting the appropriate level of LOE is to require the Program Manager’s approval on all LOE accounts. While control accounts may contain a mixture of LOE and Discrete Effort, many organizations establish rules concerning the maximum allowable LOE in a control account to prevent the distortion of status; often a threshold of 20% is established. Above that threshold, a separate control account would be required for LOE work. While it is a goal to have no more LOE than is required, care must be taken not to measure work that is truly LOE. CAMs have been known to say that they were required to establish a discrete account even though the nature of the work is impractical to measure. This type of discovery by a review team can also result in a finding for use of an inappropriate earned value technique.

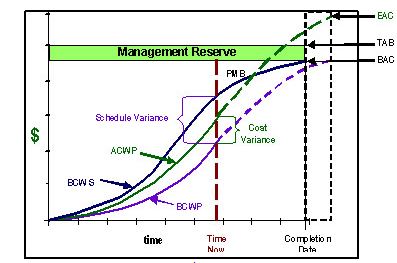

2) Misuse of Management Reserve

Management Reserve (MR) is a portion of the overall contract budget held for management control purposes and unplanned events that are within the scope of the contract. H&A has often heard in the course of our consulting or training that there are few rules regarding MR, and the restrictions are unclear. This is not quite accurate. The Integrated Program Management Report Data Item Description (IPMR DID, DI-MGMT-81861) lists four restrictions on the use of MR:

- MR shall not be used to offset cost variances.

- MR shall never be a negative value.

- If MR includes the contractor and subcontractor amounts together, the breakout shall be discussed in Format 5.

- Amounts from MR applied to WBS elements during the reporting period shall be listed in Block 6.b of Format 3 and explained in Format 5.

- Format 5: Identify the sources and uses of MR changes during the reporting period. Identify the WBS elements to which MR was applied and the reasons for its application.

The EIA-748-C Standard adds a few more caveats for MR:

- Held for unexpected growth within the currently authorized work scope, rate changes, risk and opportunity handling, and other program unknowns.

- May be held at the total program level or distributed and controlled at lower management levels.

- Held for current and future needs and is not used to offset accumulated overruns or under runs.

- Is not a contingency that can be eliminated from prices during subsequent negotiations or used to absorb the cost of program changes.

- Must not be viewed by a customer as a source of funding for added work scope. This is especially important to understand that it is a budget item and that it is not for added work scope.

In addition, the Defense Acquisition University Evaluation Guide (EIA 748 Guideline Attributes & Verification Data Traces) requires that the internal MR Log be reconciled with the IPMR (or CPR).

The specific nature of the above requirements reflects the types of abuse experienced with the MR budgets. The EVM SDD should establish specific organizational guidelines for the application of MR; however, those rules and the organization’s practices must fall within the bounds established by the EIA-748-C and the appropriate Data Item Description (DID).

The discrepancies found in recent reviews take two primary forms: inappropriate application of MR in the current accounting period and poor reporting and discussion involving MR use in the IPMR/CPR Formats 3 and 5. With the exception of rate or process changes, all applications of MR must be made in association with additional work scope authorized to control accounts. Because of the prohibition in the requirements regarding the offset of overruns or underruns, applications in the current period can be far more suspicious than in future periods. Care must be taken to fully justify the timing and use of MR in terms of additional scope. All applications of MR must have a full accounting in Formats 3 and 5 of the IPMR (or CPR).

Most Common Corrective Action Plans

Response to these discrepancies is usually a matter of policy, training, and discipline. The EVM SDD must contain a policy that enforces the rules in the guidance documents mentioned above, as well as document who has the authority for approval of MR application (generally the Program Manager). Those responsible for authorization of MR must be familiar with the approval policies, and their support staff must ensure there is complete visibility in the customer reporting and reconciliation to the program logs. One of the more common corrective actions is to structure the IPMR (or CPR) Format 5 so that reporting of MR transactions meets the intent of the guidance cited above.

3) Administrative Control Account Managers (CAMs)

The role of the CAM can change across organizations, and there is no standard set of criteria that defines the CAM’s duties. The National Defense Industrial Association (NDIA) Integrated Program Management Division (IPMD) Earned Value Management Systems Intent Guide states that “The control account manager is responsible for ensuring the accomplishment of work in his or her control account and is the focal point for management control”. The requirements for management control can be defined as having three essential attributes for the role of the CAM: responsibility, authority, and accountability. These attributes assume ownership of the technical, schedule and cost aspects of the scope authorized to a Control Account Manager (CAM). It is not always the case that the CAM must be the technical expert over the scope of the control account; sometimes that is the role of the “performing organization” rather than the “responsible organization”.

Primarily through discussion with the CAMs, it is easy to assess if they fail in performing any or all three of the above essential attributes. Because being a CAM brings a set of duties that are over and above those of a technical manager or engineer, the CAM’s role is often not a welcomed addition and some organizations hand it over to employees who have little knowledge of, or responsibility for, the effort. A comment on a Corrective Action Request (CAR) for an organization that was employing Administrative CAMs was “CAM does not stand for ‘Control Account Monitor’”. The role of the CAM does include necessary administrative responsibilities; such as, reporting status, maintaining records, and developing analysis for the control accounts. However, these cannot be the only functions the CAM performs.

A CAM should be active in the development of the control account plans in the IMS and EVM Systems, including being the primary architect for defining the tasks, logic for the schedule and the adequacy of the budget. The CAM should be the primary contact for the Program Manager regarding the control account, including risk management and corrective action planning. The CAM should also have the authority to assign and coordinate work performed by other organizations. The CAM should have enough knowledge of the scope and the executing environment to develop a realistic forecast of costs beyond that of mathematical extrapolation. If control accounts contain subcontracted work, the CAM is also responsible for management of that subcontractor effort.

Most Common Corrective Action Plans

Choosing the right personnel to fulfill the requirements of the CAM role can be difficult. One of the first considerations is the appropriateness of the organization that is given the responsibility for management. An example is for material control accounts where the organization responsible during a program’s development phase may not be appropriate for the production phase. It is very important for the contractor when submitting the corrective action plan (CAP) to treat the job of the CAM as being critical to project success, and not one relegated to people in the organization who do not have responsibility, authority, or accountability.

The Correction Action Plan should also include a list of essential CAM attributes, and be very clear on the responsibilities and authority of the CAM role. Companies should make a commitment to ensure that the position is considered critical and not just created to fulfill the requirements of earned value. This can be demonstrated by not only choosing the right individuals to perform the functions, but also providing the necessary resources, training, and support to function successfully.

This completes our 5 part series. Thank you for your readership.

If you have any questions or would like to inquire about our services, please feel free to contact us.

Common Problems Found in EVMS and Recommended Corrective Actions – Part 5 Read Post »