Formal Reprogramming: OTB or OTS Best Practice Tips

As a result of an Earned Value Management System (EVMS) compliance or surveillance review, the Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA) or DOE Office of Project Management (PM-30) may issue a corrective action request (CAR) to a contractor. H&A earned value consultants frequently assist clients with developing and implementing corrective action plans (CAPs) to quickly resolve EVMS issues with a government customer.

A recent trend our earned value management consultants have observed is an uptick in the number of CARs being issued related to over target baselines (OTB) and/or over target schedules (OTS). On further analysis, a common root cause for the CAR was the contractors lacked approval from the contracting officer to implement the OTB and/or OTS even though they had approval from the government program manager (PM).

So why was a CAR issued? It boils down to knowing the government agency’s contractual requirements and EVMS compliance requirements.

What is an OTB/OTS and when it is used?

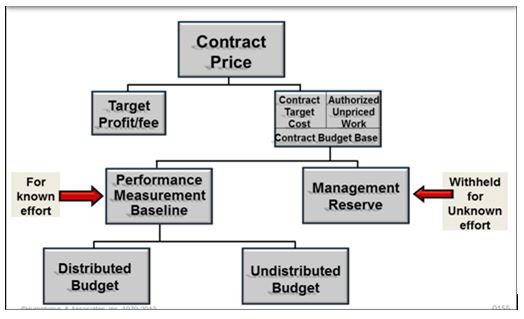

During the life of a contract, significant performance or technical problems may develop that impact schedule and cost performance. The schedule to complete the remaining work may become unachievable. The available budget for the remaining work may become decidedly inadequate for effective control and insufficient to ensure valid performance measurement. When performance measurement against the baseline schedule and/or budgets becomes unrealistic, reprogramming for effective control may require a planned completion date beyond the contract completion date, an OTS condition, and/or a performance measurement baseline (PMB) that exceeds the recognized contract budget base (CBB), an OTB condition.

An OTB or OTS is a formal reprogramming process that requires customer notification and approval. The primary purpose of formal reprogramming is to establish an executable schedule and budget plan for the remaining work. It is limited to situations where it is needed to improve the quality of future schedule and cost performance measurement. Formal reprogramming may be isolated to a small set of WBS elements, or it may be required for a broad scope of work that impacts the majority of WBS elements.

Formal reprogramming should be a rare occurrence on a project and should be the last recourse – all other management corrective actions have already been taken. Typically, an OTB/OTS is only considered when:

- The contract is at least 35% complete with percent complete defined as the budgeted cost for work performed (BCWP) divided by the budget at completion (BAC);

- Has more than six months of substantial work to go;

- Is less than 85 percent complete; and

- The remaining management reserve (MR) is near or equal to zero.

A significant determining factor before considering to proceed with a formal reprogramming process is the result from conducting a comprehensive estimate at completion (CEAC) where there is an anticipated overrun of at least 15 percent for the remaining work.

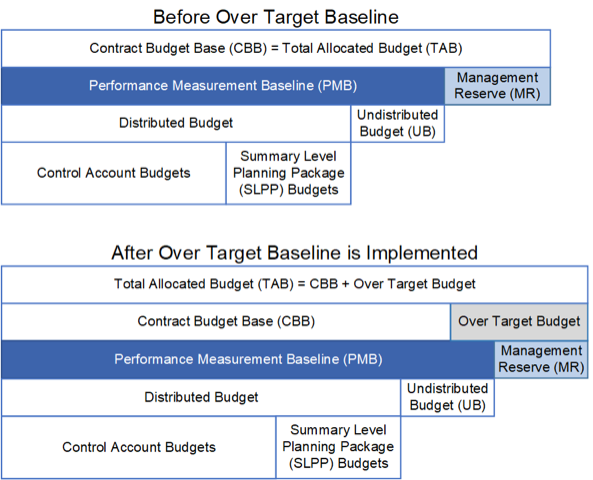

When an OTB is approved, the total allocated budget (TAB) exceeds the CBB, this value referred to as the over target budget. Figure 1 illustrates this.

When an OTS is approved, the same rationale and requirements for an OTB apply. The planned completion date for all remaining contract work is a date beyond the contract completion date. The purpose of the OTS is to continue to measure the schedule and cost performance against a realistic baseline. The process must include a PMB associated with the revised baseline schedule. Once implemented, the OTS facilitates continued performance measurement against a realistic timeline.

Contractual Obligations

An OTB does not change any contractual parameters or supersede contract values and schedules. An OTS does not relieve either party of any contractual obligations concerning schedule deliveries and attendant incentive loss or penalties. An OTB and/or OTS are implemented solely for planning, controlling, and measuring performance on already authorized work.

Should you encounter a situation where it appears your best option is to request an OTB and/or OTS, the DoD and DOE EVMS policy and compliance documents provide the necessary guidance for contractors. It is imperative that you follow agency specific guidance to prevent being issued a CAR or your OTB/OTS request being rejected.

DoD and DOE both clearly state prior customer notification and contracting officer approval is required to implement an OTB and/or OTS. These requirements are summarized the following table.

| Reference | DoD/DCMA1 | DOE |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory | DFARS 252.234-7002 Earned Value Management System “(h) When indicated by contract performance, the Contractor shall submit a request for approval to initiate an over-target baseline or over-target schedule to the Contracting Officer.” | Guide 413.3-10B Integrated Project Management Using the EV Management System 6.1.2 Contractual Requirements. “…if the contractor concludes the PB TPC and CD-4 date no longer represents a realistic plan, and an over-target baseline (OTB) and/or over-target schedule (OTS) action is necessary. Contracting officer approval is required before implementing such restructuring actions…” Attachment 1, Contractor Requirements Document “Submit a request for an Over-Target Baseline (OTB) or Over-Target Schedule (OTS) to the Contracting Officer, when indicated by performance.” |

| EVMS Compliance2 | Earned Value Management System Interpretation Guide (EVMSIG)3 Guideline 31, Prevent Unauthorized Revisions, Intent of Guideline “A thorough analysis of program status is necessary before the consideration of the implementation of an OTB or OTS. Requests for establishing an OTB or an OTS must be initiated by the contractor and approved by the customer contracting authority. | EVMS Compliance Review Standard Operating Procedure (ECRSOP), Appendix A, Compliance Assessment Governance (CAG) Subprocess G. Change Control G.6 Over Target Baseline/Over Target Schedule Authorization “An OTB/OTS is performed with prior customer notification and approval.” See Section G.6 for a complete discussion on the process. |

| Contractor EVM SD4 | DCMA Business Process 2 Attachment, EVMS Cross Reference Checklist (CRC), Guideline 31. “b. Are procedures established for authorization of budget in excess of the Contract Budget Base (CBB) controlled with requests for establishing an OTB or an OTS initiated by the contractor, and approved by the customer contracting authority?” | DOE ESCRSOP Compliance Review Crosswalk (CRC), Subprocess Area and Attribute G.6 “Requests for establishing an OTB or an OTS are initiated by the contractor and approved by the customer contracting authority.” |

Notes:

- When DoD is the Cognizant Federal Agency (CFA), DCMA is responsible for determining EVMS compliance and performing surveillance. DCMA also performs this function when requested for NASA.

- Along with the related Cross Reference Checklist or Compliance Review Crosswalk, these are the governing documents the government agency will use to conduct compliance and surveillance reviews.

- For additional guidance, also see the DoD EVM Implementation Guide (EVMIG) , Section 2.5 Other Post-Award Activities, 2.5.2.4 Over Target Baseline (OTB) and Over Target Schedule (OTS). The EVMIG provides more discussion on the process followed including the contractor, government PM, and the contracting authority responsibilities.

- Your EVM System Description (SD) should include a discussion on the process used to request an OTB/OTS. The EVM SD content should be mapped to the detailed DCMA EVMS guideline checklist or the DOE Compliance Review Crosswalk (subprocess areas and attributes) line items.

Best Practice Tips

The best way to avoid getting a CAR from a government agency related to any OTB or OTS action is to ensure you have done your homework.

- Verify your EVM SD, related procedures, and training clearly defines how to handle this situation. These artifacts should align with your government customer’s EVMS policy and regulations as well as compliance review guides, procedures, and checklists. Be sure your EVM SD or procedures include the requirement to notify and gain approval from the government PM and contracting officer, as well as what to do when the customer does not approve the OTB or OTS. Also discuss how to handle approving and managing subcontractor OTB/OTS situations; the prime contractor is responsible for these actions. Your EVMS training should also cover how to handle OTB/OTS situations. Project personnel should be aware of contractual requirements as well as your EVMS requirements and be able to demonstrate they are following them.

- Maintain open communication with the customer. This includes the government PM as well as the contracting officer and any other parties involved such as subcontractors. Requesting an OTB or OTS should not be a surprise to them. Verify a common agreement has been reached with the government PM and contracting officer that implementing an OTB or OTS is the best option to provide visibility and control for the remaining work effort.

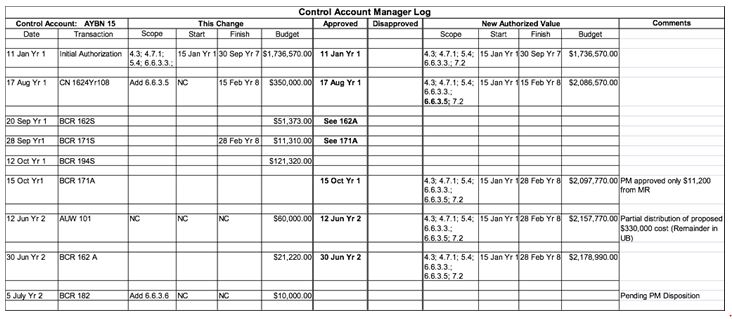

- Verify you have written authorization from the government PM and the contracting officer before you proceed with implementing an OTB or OTS. You will need this documentation for any government customer EVMS compliance or surveillance review. Your baseline change requests (BCRs) and work authorization documents should provide full traceability for all schedule and budget changes required for the formal reprogramming action.

Does your EVM SD or training materials need a refresh to include sufficient direction for project personnel to determine whether requesting an OTB or OTS makes sense or how to handle OTB/OTS situations? H&A earned value consultants frequently help clients with EVM SD content enhancements as well as creating specific procedures or work instructions to handle unique EVMS situations. We also offer a workshop on how to implement an OTB or OTS . Call us today at (714) 685-1730 to get started.

Formal Reprogramming: OTB or OTS Best Practice Tips Read Post »