Understanding the As Late As Possible (ALAP) Scheduling Option in Practical Terms

Many project professionals have spent entire careers without ever using the As Late As Possible (ALAP) scheduling option, although the underlying idea feels familiar. Why? Because it’s very similar to the “just-in-time” concept widely used in manufacturing and logistics.

In materials management, just-in-time means having what you need arrive exactly when you need it, minimizing storage costs and reducing inventory. The same principle can apply to project labor, but with some important cautions.

The “Right Time” for Project Work

On development or design projects, doing work too early can be counterproductive. If designs change, early work may become obsolete, forcing costly rework. The “right time” to perform a task is often determined by schedule logic. In some cases, however, it can also be guided by the ALAP constraint.

Before we explore when ALAP makes sense, let’s quickly review the two primary constraint options in Microsoft Project (and most other scheduling tools).

ASAP – As Soon As Possible

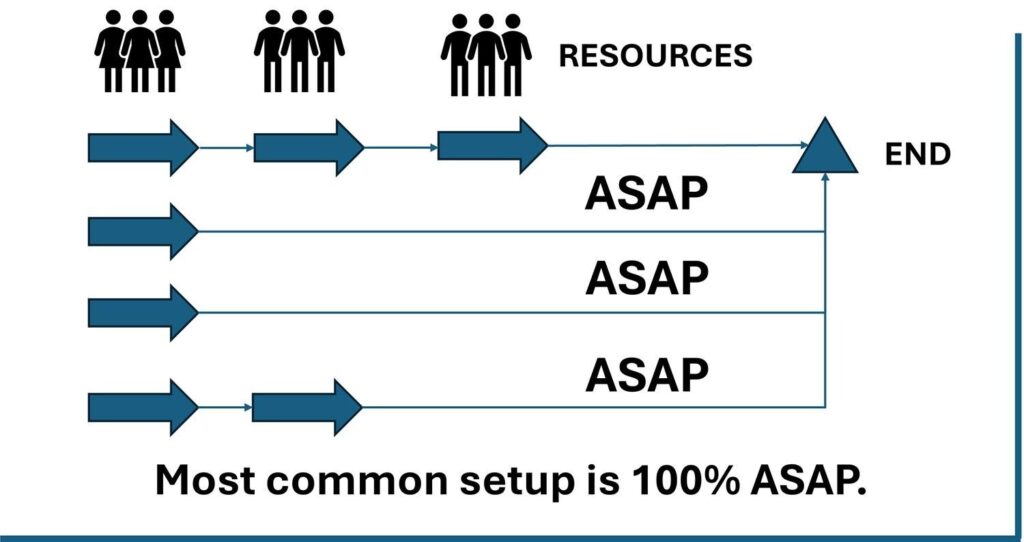

As soon as possible:

- Is the default setting for forward-scheduled projects (when you set a project start date).

- Means tasks are pushed as early as possible, immediately after their predecessors finish.

- Is ideal when you want the earliest possible completion and clear visibility into float/slack.

In an ASAP chain, every task begins at the earliest opportunity, pushing resources as far to the left as possible on the Gantt chart as illustrated in Figure 1.

ALAP – As Late As Possible

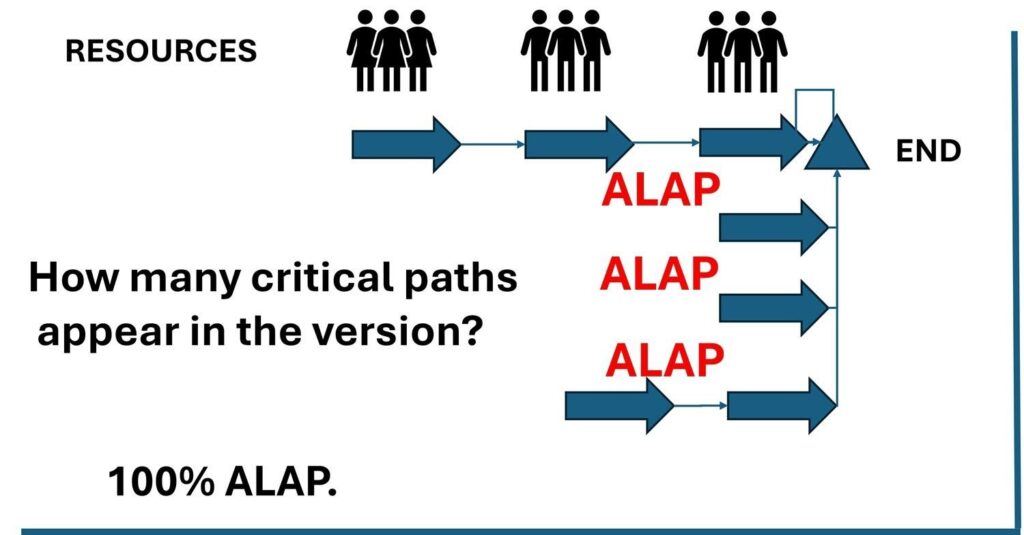

As late as possible:

- Means tasks are scheduled as late as possible without delaying the successor or project finish date.

- Is used in backward-scheduled projects (those planned from a fixed finish date) or when you want to defer work until the last responsible moment.

- Microsoft Project automatically places each task at the latest feasible start date that still satisfies all constraints.

Switching a chain of tasks to 100% ALAP dramatically shifts all work to the right on the timeline as illustrated in Figure 2. The impact on management is significant: Every task now has zero total slack, which means any delay, even one day, directly delays the project finish. Multiple paths can appear “critical,” making control and reporting more complex.

When ALAP Makes Sense

There are legitimate reasons to use ALAP selectively. For example:

- When a task consumes resources you don’t want engaged early (e.g., expensive equipment rental or specialized consultants).

- For just-in-time deliveries or procurements where early completion has no benefit.

- When modeling backward scheduling. For instance, working from a fixed delivery date toward today.

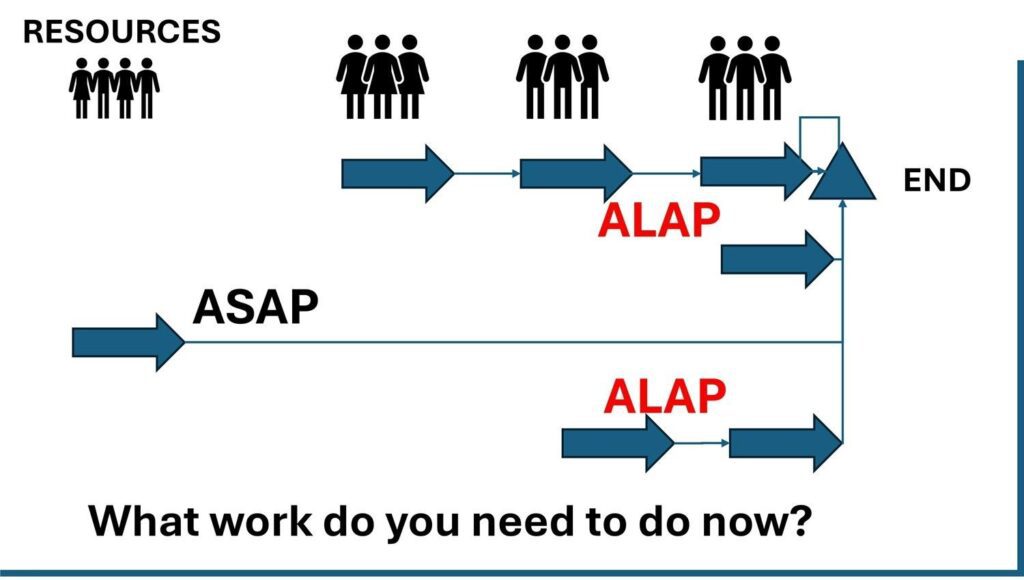

- A mixed schedule. Mostly ASAP but with a few ALAP tasks can balance flexibility, cost control, and realism as illustrated in Figure 3.

A Real-World Example

One of H&A’s senior scheduling consultants once faced this exact dilemma while helping to prepare a multi-year, multi-billion-dollar defense proposal for a project with strict annual funding limits.

With less than two weeks before the submission deadline, the Proposal Director was exasperated: “I keep asking the engineers what can be delayed! Why does everything have to happen up front? The front-loaded schedule is blowing our funding cap!”

A quick inspection revealed the problem: every task was set to ASAP. The entire effort was jammed toward the beginning of the timeline, creating a massive early demand for resources. After several failed attempts to persuade the engineers to move work later, the consultant proposed something unconventional: “Let’s flip the question. Instead of asking what can we delay, let’s ask what must be done now.”

The H&A scheduling consultant converted the entire schedule to ALAP, instantly shifting all work to the far right of the timeline. The resulting view inverted the problem, from overspending early to under-spending, and gave the team a new way to discuss priorities.

In meetings, engineers were asked to move tasks from ALAP to ASAP one at a time, stopping when the annual funding limit was reached. The discussion changed from “Why can’t we do this now?” to “What can we afford to do this year?”

The result wasn’t elegant, but it solved the immediate problem: the funding limits were clearly observed, the resource profile became manageable, and the trade-offs were visible to everyone.

How ALAP Affects Critical Path and Risk

Because ALAP tasks consume all available float, they appear critical even when they may not truly drive the project finish. This can obscure the actual critical path, making it difficult for project managers to distinguish between genuine schedule risks and artificial ones. In Earned Value Management (EVM) environments, this matters. Earned value metrics depend on knowing which tasks drive completion. Excessive use of ALAP can lead to misleading forecasts and distort DCMA data quality metrics such as the Total Float test and the Critical Path test. For this reason, auditors often recommend using ALAP sparingly and documenting the rationale wherever it’s applied.

Note: in a sophisticated scheduling environment, it is possible to make a copy of the integrated master schedule (IMS) and revert to ASAP to look for critical paths in the normal sense.

Combining ALAP with Other Constraints

In practice, project managers often use a blend of constraint types. For example, you can combine ALAP with “Must Finish On” or “Start No Earlier Than” dates to simulate external dependencies such as contract milestones, funding release dates, or material delivery windows. This hybrid approach allows the schedule to model reality while maintaining logical control. However, it’s important to track these constraints carefully. Too many “hard” constraints of any type can reduce the schedule’s dynamic nature and make automated forecasting less accurate.

Guidance from Industry and Agencies

Industry and government scheduling guides consistently advise restraint when using ALAP. The DCMA data quality tests consider the presence of ALAP tasks as a potential red flag because they can mask schedule float and obscure the true drivers of program completion. Similarly, the GAO’s Schedule Assessment Guide recommends minimizing artificial constraints and using logic-driven sequencing whenever possible. ALAP may be appropriate for modeling constrained resources or fixed delivery milestones, but it should always be justified and documented. Within DoD and NASA programs, reviewers often require clear evidence that ALAP usage is intentional, controlled, and limited to well-understood modeling cases. It should never be used as a workaround for poor sequencing.

Key Takeaways

- ASAP emphasizes early starts, clear float visibility, and traditional forward scheduling.

- ALAP emphasizes delayed starts, tighter resource control, and is useful in backward or funding-constrained planning.

- Use ALAP sparingly and intentionally as it can obscure float and create multiple critical paths.

- In creative problem-solving, toggling between ASAP and ALAP can reveal insights about timing, funding, and necessity that might otherwise remain hidden.

Final Thoughts

The ALAP constraint is a powerful but double-edged tool. It can simplify discussions about funding limits, resource phasing, and timing priorities, but it also carries risk if used indiscriminately. Like most features in commercial off the shelf (COTS) scheduling tools, its value depends on the user’s intent and discipline. The best project schedules blend logic, transparency, and flexibility. Understanding when to use ALAP (and when not to) can make the difference between a reactive plan and a truly managed one.

Interested in Learning How to Use More Advanced Scheduling Techniques?

Master schedulers skilled at asking the right questions to solve project management challenges hone their craft based on years of experience and working with other scheduling experts. There are always opportunities to learn more. H&A routinely offers basic, advanced, and tailored scheduling workshops taught by senior master schedulers with decades of experience in all types of project environments using common scheduling tools such as Microsoft Project and Oracle Primavera P6. Give us a call today to get started.

Humphreys and Associates also offers basic and advanced EVMS training as well as tailored EVMS training that aligns with a client’s EVM System Description.

Understanding the As Late As Possible (ALAP) Scheduling Option in Practical Terms Read Post »