Management Reserve; Comparing Earned Value Management (EVM) and Financial Management Views of “Reserves”

Perhaps you have witnessed the collision of earned value management’s views on “management reserve” with the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) and the finance department’s views on “balance sheet reserves.” Most companies tend to organize EVM, the function, reporting to either the programs’ organization or to the finance organization. Either will work but either can fail if the two organizations do not understand the interest of the other.

Perhaps you have witnessed the collision of earned value management’s views on “management reserve” with the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) and the finance department’s views on “balance sheet reserves.” Most companies tend to organize EVM, the function, reporting to either the programs’ organization or to the finance organization. Either will work but either can fail if the two organizations do not understand the interest of the other.

In this article we will outline three areas. The first will be EVM and Management Reserve (MR). The second will be finance and balance sheet “contingencies, loss provisions, or reserves.” The third will compare the two views and identify where they are similar and where they differ.

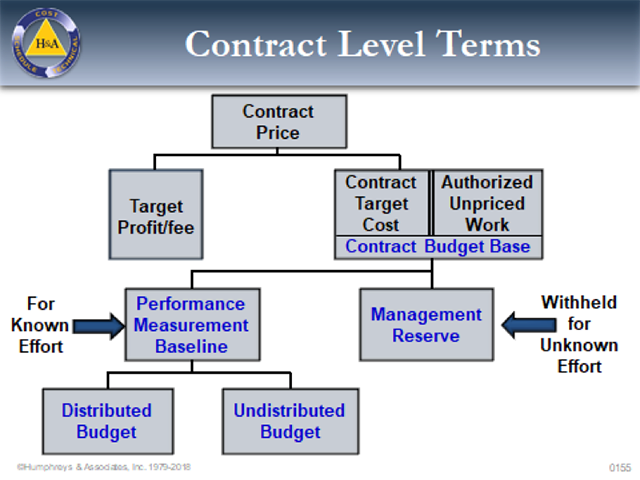

We will use two terms for both EVM and Financial Management; “in play” and “on the sideline.” “In play” for EVM means that it is in your Performance Measurement Baseline (PMB) and Budget at Completion (BAC). “On the sideline” for EVM means “not in scope” therefore in MR. “In play” for financial management means recorded on the balance sheet (e.g.: current liability; an accrued liability). “On the sideline” for financial management means not recorded on the balance sheet, because it is more likely than not that a liability has been incurred. If material, however, it will likely be disclosed in the notes to the financial statements, even if it is not recorded on the balance sheet.

Earned Value Management and Management Reserve

A program manager and his or her team must deal with – mitigate – risk or be consumed by those risks as they become issues. There are two types of risks, known and unknown. The known risks are entered into a risk register, and their likelihood and consequence are determined. Mitigation for those known risks is done at the activity level in a program’s Integrated Master Schedule (IMS) (Planning and Scheduling Excellence Guide — PASEG page 141, ¶ 10.3.1). Mitigation of known risks is part of the PMB (in the BAC) and is therefore “in play.”

The second type of risk – unknown or unknowable risks – are covered by management reserve if within the Scope of Work (SOW) of the existing contract. If contractor and customer conclude that the realized risk is outside the existing contract, then an Engineering Change Proposal (ECP) would likely be created by the contractor; and a contract modification would be issued by the authorized customer contracting officer if they agreed. The program manager should ask this question of his team: what work is “at risk” and what work is not “at risk?” Does labor or material present more risk? Management reserve “is an amount of the overall contract budget held for management control purposes and for unplanned events” (Integrated Program Management Report–IPMR DI-MGMT-81861 page 9, ¶ 3.2.4.6). Management reserve is “on the sidelines.” MR has no scope. MR is not earmarked. MR stands in waiting.

Earned Value Management Reserve (MR) Compared To Financial Management “Contingency”

Because the audience reading this blog is most likely from the EVM community, I’ll offer a Financial Management example of a company that faces many risks and must manage those risks or be consumed by them. Altria Group, Inc. and Subsidiaries (stock symbol: MO) are in the tobacco, e-Vapor and wine business. Altria’s history clearly shows that the company measures and successfully mitigates the risks they face. Altria faces a blizzard of litigation each year and must protect its shareholders from that risk. So how does Altria manage known risks (mostly from litigation) and how does Altria handle unknown risks?

Altria is a publicly traded company and its annual report (10K) is available on-line to the public. This data is from their 2014 annual report.

I am an MBA, not a CPA, so I’ll stick to Altria’s 2014 balance sheet. For those not familiar with financial statements, a balance sheet has on its left hand side all of a company’s assets – what the company owns and uses in its business (current assets = cash, accounts receivable, inventory; long term assets = property, plant and equipment). The right hand side of a company’s balance sheet shows current and non-current liabilities and shareholders’ equity. The top right hand side of the balance sheet includes current and non-current liabilities (accounts payable, customer advances, current and long-term debt, and accrued liabilities like income taxes, accrued payroll and employee benefits, accrued pension benefits and accrued litigation settlement costs) and the bottom of the right hand side of the balance sheet includes shareholders’ equity consisting of common and preferred stock, paid in capital and retained earnings.

Altria’s 2014 annual report shows under current liabilities; accrued liabilities; settlement charges (for pending litigation Contingency note # 18) a value of $3.5 billion dollars. The 2013 amount was $3.391 billion dollars.

So Altria has “in play” $3.5B for litigation for 2014. In financial terms, Altria has recorded $3.5 billion in expense related to the litigation, probably over several years as it became more likely than not that a liability had been incurred and was reasonably estimable. In EVM terms Altria has $3.5B in their baseline, or earmarked, or in scope for litigation (court cases).

What happens if Altria ultimately has more than $3.5B in litigation settlement costs? What does Altria have waiting on the “sidelines” to cover the unknown risks? Essentially Altria has on its balance sheet waiting “on the sidelines” $3.321 billion in cash and the ability to borrow additional funds or perhaps to sell additional shares of stock to fund the settlement costs. In EVM terms Altria has $3.5B in its baseline (on its balance sheet) to manage the risks associated with litigation. Altria’s market capitalization at the market close on May 17, 2015 was $52.82 billion and its 2014 net revenues were $24.522 billion. It is reasonable to understand that Altria has more than enough MR.

Differences Between EVM MR and Financial Management Balance Sheet Reserves

In EVM, MR is only released to cover unplanned or unknown events that are in scope to the contract but out-of-scope to any control account. A cost under-run is never reversed to MR, and a cost over-run is never erased with the release of MR into scope.

In industry in general, and Altria in particular, if the “in play” current liability for settlement charges of $3.5B are not needed (an under-run), then Altria will reverse a portion of the existing accrued liability into income, thereby improving profitability. If Altria’s balance sheet reserve of $3.5B is insufficient, then Altria’s future profits will be reduced as an additional provision will be expensed to increase the existing reserve (an over-run).

[Humphreys & Associates wishes to thank Robert “Too Tall” Kenney for authoring this article.]