Confusing QBD Baseline Changes with QBD EAC Changes

Quantified Backup Data

Quantified Backup Data (aka QBD) has become a requirement for contractors who make use of the “Percent Complete” Earned Value Technique (EVT). This requirement is actually a good thing because it helps eliminate the guesswork previously cited as a flaw in the percent complete EVT. Unfortunately, it has become a good idea gone bad through over-implementation.

The primary problem: Confusing “QBD Baseline Changes” with “QBD EAC Changes.” Many contractors are unnecessarily bogging down their change control process with requests to “change the QBD” when all that is really changing is the detail behind some of the steps in the QBD.

The Cake Example

Let’s take a simple, practical example of baking a cake to illustrate the difference. What follows is an approach found online from one baking company. The example weights have been added by the author.

| 10 Basic Steps to Making Any Cake | Step Weight (Percentage of Process) |

| 1. Select the recipe for the type of cake | 2% |

| 2. Select and prepare (grease) the pans | 2% |

| 3. Preheat the oven | 2% |

| 4. Prepare the ingredients | 30% |

| 5. Mix the ingredients | 40% |

| 6. Put batter in pan and bake the cake | 5% |

| 7. Remove the cake from the pan | 2% |

| 8. Let the cake cool | 2% |

| 9. Make the frosting | 10% |

| 10. Frost the cake | 5% |

For the context of this blog, this bakery’s approach IS the Cake (baseline) QBD. Chocolate cake, pound cake, apple cake, one layer cake, multi-tiered cake, birthday cake, or wedding cake. It does not matter. This bakery approaches making any type of cake with this QBD. Some cakes, however, are more complex than other cakes – not all cakes are created equal.

Steps 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, and 8 are standard and would likely have the same “budget weight” in the Cake QBD, regardless of the type of cake. Steps 4, 5, 9, and 10, on the other hand, might be more involved for a complex cake. Remember: Complexity does not change the Cake (baseline) QBD!

Simple Cake vs Complex Cake

Let’s look at the Cake QBD to see how different types of cakes are handled by comparing a Simple Cake, Vanilla with Chocolate Frosting, to a Complex Cake, Apple Walnut German Chocolate.

Follow Steps 1, 2, and 3 (unchanged)

Step 4: Prepare the ingredients

Simple Cake: Gather eggs, milk, flour, cake batter mix.

Complex Cake: Gather eggs, milk, flour, sour cream, walnuts, apples, coconut, lemon juice, pre-cooked apples, chopped walnuts, shaved coconut.

Step 5: Mix the ingredients

Simple Cake: Blend together the eggs and milk. Then add in the flour and dry cake batter mix.

Complex Cake: Blend together the eggs and milk. When smooth, fold in sour cream. Then add in the flour and the cake batter mix. When thoroughly blended, add cooked apples, lemon juice, chopped walnuts, and shaved coconut. Blend until evenly mixed.

Follow Steps 6, 7, and 8 (unchanged)

Step 9: Make the frosting

Simple Cake: Pre-made chocolate frosting mix.

Complex Cake: German chocolate frosting mix, add coconut, add chopped walnuts, mix gently until additions are evenly spread throughout mix.

Step 10: Frost the cake

Simple Cake: Frost between layers, frost top layer, frost side of cake.

Complex Cake: Frost between layers, frost top layer, frost side of cake. Apply apple wedges on top of the frosted layer, sprinkle on more chopped walnuts, apply frosting flowers around bottom with frosting tool.

As you can see, the 10 Step Cake QBD did not change throughout this process. What did change was the set of ingredients and some of the added lower level steps within the QBD Steps 4, 5, 9, and 10. This might add some cost (EAC) for the added ingredients, and for the additional labor of precooking, chopping, and shaving. However, in the overall context of the Cake Baking process, the steps (QBDs) and the associated weighting of each QBD remained the same. In this bakery, all that changes would be the forecast cost (EAC) for the complex cake over the simple one – i.e., no baseline change request (BCR) is needed to change the QBD!

QBD vs EAC

In this simple example, the QBD is Baking a Cake. It is not “Baking an Apple Walnut German Chocolate Cake.” If this were the QBD, then this bakery would have hundreds of QBDs, depending on the different types and complexities of cakes the bakery could possibly make. For example, would you want a separate QBD for a birthday cake to say “Happy Birthday Johnny”? No, that would be a cost (EAC) for the Frosting QBD Step. The QBD EACs affected would be Step 9, Make the frosting, and Step 10, Frost the cake. Rather than hundreds of QBDs, this bakery has ONE! The cost (EAC) of a cake varies based on the complexity and content of the cake.

This QBD approach applies to any number of other processes. Here are a couple of others:

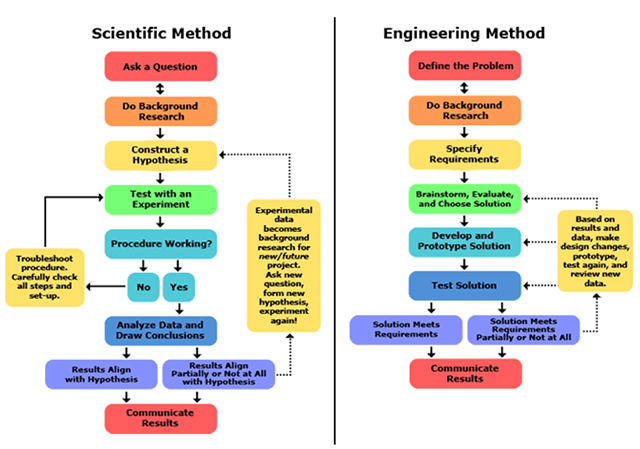

Above: Basic idealized steps of the scientific method (left) and engineering design process (right).

*From sciencebuddies.org

In this case, the complexity of the problem being addressed might impact the amount of research required or the experiments or brainstorming solutions needed. This could dictate the number of times the yellow box to the right (the re-do box) is required. However, the approach is exactly the same until the process achieves the “Results Align with Hypothesis” (for the scientific method) or the “Solution Meets Requirements” (for the engineering design method), and the results are communicated.

The House Example

Another practical hands-on example could be the steps in building a house:

- Grading and site preparation

- Foundation construction

- Framing

- Installation of windows and doors

- Roofing

- Siding

- Electrical Rough-In

- Plumbing Rough-In

- HVAC Rough-In

- Insulation

- Drywall

- Trim

- Painting

- Finish electrical

- Bathroom and kitchen counters and cabinets

- Finish plumbing

- Carpet and flooring

- Finish HVAC

- Hookup to water main, or well drilling

- Hookup to sewer or installation of a septic system

- Punch list

As with baking a cake, for this builder, the size of the house will make a difference in how much the house will cost, but the QBD approach to building each house is the same. Some of the lower level activities below each QBD step might be more involved. For example, Step 2, Foundation construction might be more involved if the house is to have a basement. Other steps might be more or less involved. Step 17, Carpet and flooring might stop at the concrete slab because the buyers want to have their own custom flooring and carpeting put in later. None of these examples change the 21 QBDs this contractor follows when building a house. The lower level activities will simply cost more or less than other models (the EAC – not the baseline QBD), but the overall weighting of the QBDs for “Building a House” would be the same.

The Scope Has Not Changed

The same approach can be used for engineering drawings, conducting inspection testing, developing a drug for FDA approval, a scientific approach to a health problem, or any other process that follows a standardized approach toward its end product. The key is segregating the EAC aspect from the baseline QBD aspect of the process. Don’t get mired in constantly trying to “change the QBD” when it is not needed.

If the basic steps do not change, the QBD is not changing! More or less granularity in the lower level details beneath each QBD step is handled in EAC space and will be reflected in the cost of the task. You do not need to change the budget. Why? Because the scope has not changed.

Repeat with emphasis. THE SCOPE HAS NOT CHANGED – you are still:

- Doing an engineering drawing,

- Resolving a scientific or engineering design problem,

- Building a house, or even just

- Baking a cake.

Let’s keep QBDs simple for the CAMs – and keep the change control process uncluttered.

Humphreys & Associates can help with your QBD planning and implementation. Contact us at (714) 685-1730 or email us.

Confusing QBD Baseline Changes with QBD EAC Changes Read Post »

Recently one of our consultants was instructing a session on the

Recently one of our consultants was instructing a session on the