Preventing a Communications Failure

“What we’ve got here is failure to communicate.”

From the movie “Cool Hand Luke”, you would probably remember the famous line, “What we’ve got here is failure to communicate. Some men you just can’t reach. So you get what we had here last week….”

Ask people who work on programs and projects, “From your experience, what are the top 10 reasons that projects fail?” You will nearly always find, at the top of the list, the cause as being one of poor communications. That’s right, failure to communicate, pure and simple. But maybe not so pure and not so simple.

Establish a Communications Plan

There are so many dimensions to communication that it is advisable, even necessary, to establish a communications plan. Think about all the topics we need to communicate; the list is mighty: goals, schedules, budgets, product requirements, status, problems, successes, forecasts, roadblocks, directions, and so on. So, it makes sense that we should take time to define the communications process and actions in our communications plan.

Assuming we are about to undertake a new project rather than inject ourselves into an ongoing one, we should consider the most natural first step in preventing a communications failure. Just as we must define the product requirements, we should also define the requirements for communications through an analysis. That analysis should be rigorous and should cover all apparent aspects of communications.

- What do we need to communicate?

- Who are the providers and the receivers of various communications?

- What are the form and format for the communication?

- What are the frequencies required for these communications?

Such a requirements analysis could result in a communications compliance matrix that lists the requirement and provides the method by which the requirement will be satisfied.

Formal and Informal Communication

Two major subsets of communications could be the formal and the informal. To start considering the formal we could go to the contract the Contract Data Requirements List (CDRL) and the many requirements for plans, reports, and other deliverables that are forms of communications. The contract could be the root of a large tree that grows level-by-level. For example, the contract might have the Statement-of-Work (S0W) that tells us to use the systems engineering approach and a CDRL item to provide a System Engineering Management Plan (SEMP) in which another level of communication is revealed. On major contracts the SEMP is but one of several plans that are often required and should be extremely useful in defining the communications plan. The totality of these plans is comprehensive and very detailed.

EVMS Structure

Of interest to us here in this blog is the requirement to manage the program using Earned Value Management Systems (EVMS). A properly implemented EVMS can be the key to avoiding many of the problems of communications that are rolled up into the generic problem of “poor communications.” EVMS is one for the formal requirements that can embody wide ranging forms of communications. In the EVMS we will communicate:

- Goals for scope, schedule, and budget. These are in various artifacts within the EVMS and provided to the stakeholders. Goals are the topic of the Integrated Baseline Review (IBR) to the extent that the probability of meeting the goals is assessed. Goals are clear when you have an Earned Value Management System.

- Structure for the project work, people, and resources. EVMS requires a Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) to formally define and decompose the work. That means it is open and clear to all on the project what must be done top to bottom and by whom it will be done.

Integrated Master Schedule

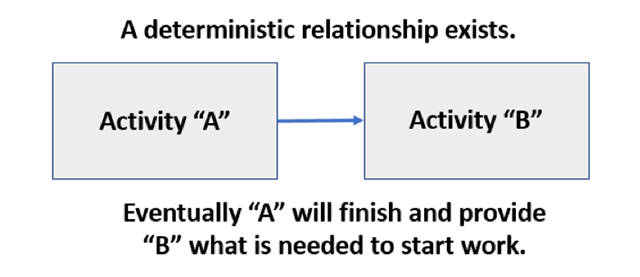

Timing for work is established in the comprehensive Integrated Master Schedule (IMS). The IMS, when properly built and coded, provides deep insight into the time plans for the project and the relationships among the players. Topics such as “external dependencies” might have once been an obscure bit of knowledge but in the IMS these are clearly defined, and the logic shows what is dependent on these external inputs to the project.

The IMS communicates the milestones that are to be achieved. Vertical integration from the work tasks to the milestones provides the links that communicate the contributors to any major event. We know what and when we must reach a certain capability, and, with the IMS, we know how we will get there and who will carry us to that goal.

Work Authorization Document

The control account Work Authorization Document (WAD) provides a formal documentation of the baseline agreement on scope, schedule, and budget for the managerial subsets of the total project work. Carving out these manageable sections of work and making formal communication of the goals and responsibilities provides a detailed communication and acceptance for the project goals and the responsibility for their accomplishment. It would be nearly impossible to get lost in the well documented baseline of an EVMS managed project.

Measuring Progress

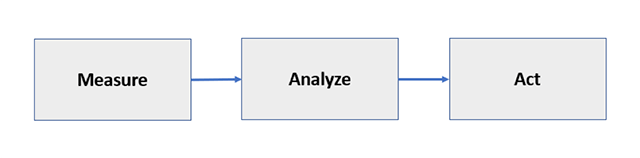

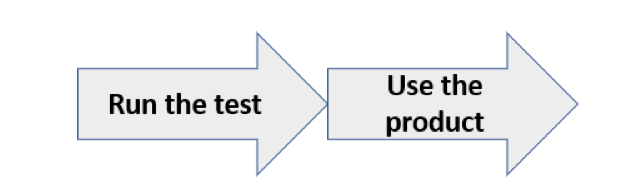

The status of our project is known by measuring our progress and reporting it formally; these are cornerstones of the EVMS.

- What should we be doing?

- What are we doing?

- Are we meeting our scope, schedule, and spending goals?

- Where are the problems?

- What are the root causes of the problems? The impacts?

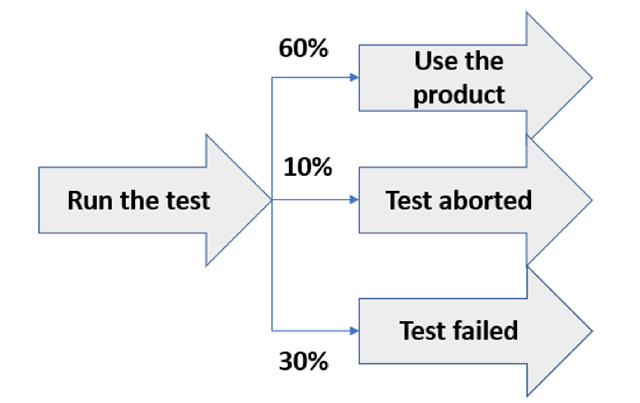

Communicating all of these up and down the hierarchies and even to the customer provides what should be open and clear communication. The generic complaint of “poor communication” often means “I was surprised.” There should be no surprises in a well run EVMS program.

Future Outcomes

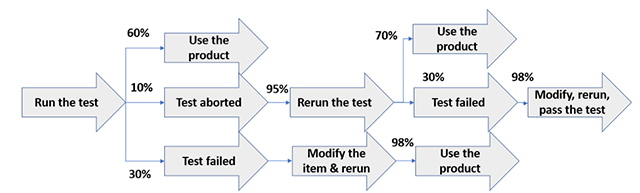

Perhaps the most important thing to communicate is the future outcome. Based on our plans and our status, we are always making projections for the potential outcomes of our project from within our EVMS. The forecast for timing is contained within the IMS. The forecast for spending is contained within the Estimate to Complete (ETC). Each period we update out view of the future and analyze what that means. We use the analysis to undertake corrective action plans that have the intended effect of getting us back on track.

Summary

So, in summary, you should see that poor communications of the items that are within the purview of the program management system (EVMS) should not happen. The EVMS should be one the main pillars of communications plans and processes to prevent a communications failure. The outcome of the program might still be less than desired, but the outcome should have been foreseen and discussed many times within the communications engendered by the EVM System. We should know what we need to do, how we are doing, and where we will end up; and those are all things we need to communicate.

Preventing a Communications Failure Read Post »