EVM Consulting – Modeling & Simulation

Forewarned is Forearmed

Forewarned is forearmed. John Farmer, of New Hampshire, said that in a letter in 1685. But that advice is most likely biblical and very much older. No matter the source of the thought, we should take it as divine guidance if we are project managers. Maybe we should have it cut into a stone tablet, so we can share it with our team members.

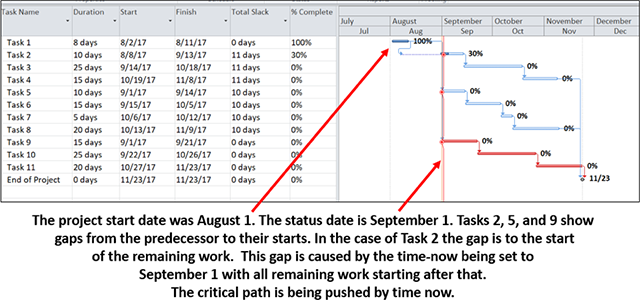

Most of our work as project managers is spent in the “controlling” phase which is made up of the three steps “measure, analyze, act.” Our EVMS and IMS exist to be able to support this management function. The measuring part is done very well in our EVMS and our IMS; we know where we are and how we got there. The analyzing is equally well handled in the IMS and EVMS. Only the management task of acting is not well supported. Generally, we lack decision making support and tools.

Deterministic Path

No matter how well constructed and how healthy our IMS is, it has a deterministic path forward. The logic links between the activities are there because we expect them to be fulfilled. Indeed, if activity “B” is a finish-to-start successor to activity “A” we fully expect that at some point activity “A” will finish and will provide its output to activity “B”. That is a single path forward and it is a deterministic path. It is also a somewhat simplistic model.

Multiple Outcomes

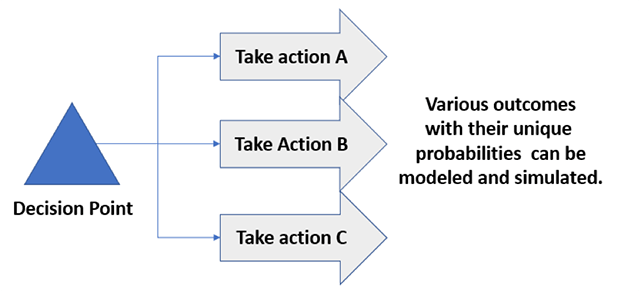

Our management system asks us to perform root cause analysis followed by corrective action. But what if there is more than one corrective action to be taken. And worse; what if the corrective actions can have multiple outcomes with each enjoying its own probability. That means multiple choices and multiple outcomes. How would we show that in our plan? How would we analyze the multiple possible futures that such a situation presents?

Happily, there are ways to model a future without a set path. And once we have the future model, there are also ways to simulate the outcomes to give the probabilities we need to decide which actions to take. We are talking about probabilistic branching, and we are saying that we can build a probabilistic map of the future to use in making decisions; especially making decisions on corrective actions.

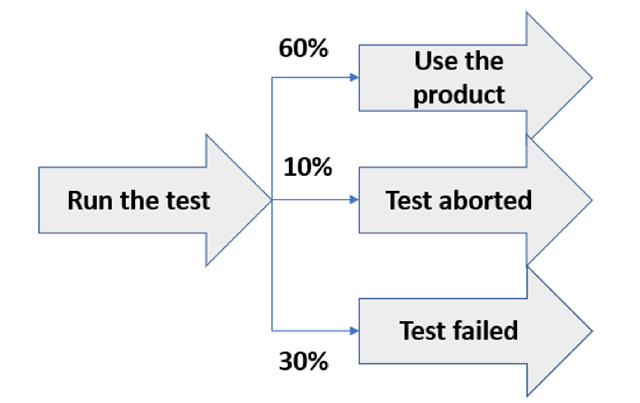

Take a simple example of running a test on the project. The expectation is that eventually we will pass the test. We will keep trying until we do. In the IMS deterministic model the test portion of the IMS might look like this:

Simulation

We can simulate this situation with different expected durations for the test. That is helpful information, but it does not explain or even capture what is going on in those different durations. It looks like we are just taking longer to do the testing but is that really what is happening? What is going on here? We certainly don’t show that.

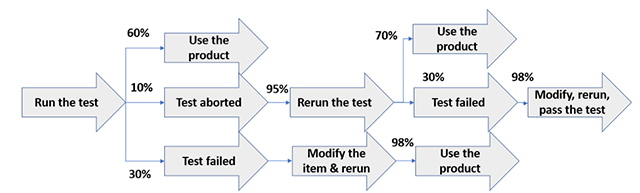

In the real world, this simple model might have three potential outcomes. There might be three paths we can take to get to the point where we use the product. Each path has a time and money cost. We might run the test and find that we passed. Or we might have to stop the test for issues on the item or the test setup. We might even fail the test and must correct something about the product to improve our chances of passing a rerun. Eventually we will get to a usable product. But what do we put in our estimate and our plan? What do we tell the resources we need? What do we tell the boss? The customer?

Full Future Model

We now have a much better understanding of the future and can explain the situation. We also can simulate the situation to find out the most likely time and cost outcomes, so we can explain the future without any histrionics or arm waving.

If the issue is important enough we can build out the full future model and simulate it.

No matter how far we pursue the model of the future, having a valid model and being able to stand on solid ground are very valuable to us as project managers.

This is not to say that we should model out complex situations as a routine in the IMS. That would be impossible, or at least prohibitively costly. We are saying that when situations arise, we need to be able to use the IMS to help us make decisions.

This type of probabilistic modeling of the future is particularly useful in defining major decision points in our plan. When we reach a decision point the IMS may have multiple branches as successors but that implies we take every branch and that is not valid. Modeling each branch and its probabilities is valid. In the example below, where the milestone represents a decision point, we have shown three possible paths to take. If each were modeled out into the future with time and cost data, we should have the information we need to choose the path we wish to pursue. Without processes and tools like this, we would be flying blind.

Future Blog Posts

This discussion will be continued in future blogs to develop a better foundational understanding of the process and power of probabilistic modeling in our EVMS.

Good information sets the stage for good decisions. The IMS and the EVMS have sufficient information to help us model the pathways ahead of our critical decisions. We just need to learn to take advantage of what we have available to us.

Find out how an experienced Humphreys & Associates EVM Consultant can help you create a full future model and simulation of your most vital EVMS Systems. Contact Humphreys & Associates at (714) 685-1730 or email us.

EVM Consulting – Modeling & Simulation Read Post »

Recently one of our consultants was instructing a session on the

Recently one of our consultants was instructing a session on the

I have read several

I have read several